To Know and to Heed

Remas, Palazzo Montini (Official Residence of the Arch-lector of Morr), Winter 2404-5

They gathered on the cloistered lawn of the Palazzo Montini. It once contained an extravagant knot garden of box-lined, symmetrically geometric divisions, of occult design, crammed with a colourful abundance of herbs and sweet-smelling flowers, but the arch-lector had ordered it transformed into an ascetically simple space of nothing but grass. He had allowed a new garden to be planted elsewhere in the grounds, to save many of the herbs, but the palazzo building itself was to be serenely uncluttered throughout, both inside the rooms, hallways and chambers, and even here in the open air of the central cloister.

The statues were marble, unpainted, being of ancient Morrite saints …

… and of the goddess Verena, wife of Morr.

Similarly plain, the building was granite and whitewashed plaster throughout.

The three rulers of the Triumverate churches were present, for as well as Arch-Lector Bernado, there was Flavio Tognazzi, High Priest of the Church of Mercopio and Luccino De Sicca, the Myrmidian Arch-Priest.

The matter they had now to discuss was of such dire importance that Bernado knew he must include these other arch-priests immediately. As a most terrible weapon of war was a critical part of that which must be discussed, he had ordered the Reman garrison captain, Sirrus Ricci and the chief artillerist, Captain Peppe Lito also to attend. The others present included guards, clerical secretaries and some clergy selected for their wit or wisdom – the young Brother Duarte, his personal secretary, had a sharp mind, while the much older Father Benvenuto had an impressive depth of experience from his many adventures.

As silence fell, Bernado took a long and deep breath of air, allowing its winter coolness to infuse him, hoping thus to invigorate his mind and thereby clarify his thoughts. He dispensed with the pleasantry of greetings, to avoid any chance of small talk intruding on this solemn occasion, and so began immediately to address the issue at hand.

“I have a most grave and urgent matter to discuss, concerning perhaps the greatest threat our city state has ever experienced.”

He waited just long enough to ensure everyone present had recognised the gravity of the situation, and then turned to his secretary, Brother Duarte.

“Duarte,” he commanded. “Read the letter.”

Duarte opened what had previously appeared to be a book but turned out to be a folder of worked leather containing several papers, and by some trick immediately perused the particular missive he was to read – parchment, with a dark red ink in a somewhat stark hand.

He too paused, clearly nervous, before he could speak. Coughing to clear his throat, he began …

“This to the arch-lector of Remas, Bernado Ugolini. Know and heed this missive and the words it show-contains, for thine own future, and that of all and everyone thou knows and loves, and that of every living creature in thy city-realm, depends on it.

The mighty Seer-Lord Urlak Ashoscrochor has proven his great and destructive power, destroying the army sent-dispatched against him at Campogrotta with his most terrible doom-bombard. The realm-land for many a league around was poison-killed, and even now the river that flow-runs through the tainted ground bears not one living fish, nor even one green-hued weed.

Understand that this was not the only such engine of war in his Great-Highness’s possession, for the diligent ingenuity of his servant legions knows no bound-limit. Nor was that engine, despite its great power-force, the most mighty that could be construct-fashioned. The engines his Almighty Highness now possess-commands, far surpass in awful power that of the first-such, for they can hurl-throw several great-grenadoes, each one containing a still more massive curse, so that cities and towns, armies and allies, indeed entire realms might perish in little more than an instant-moment.

And so, horde thy gold and silver; prepare thy labourers for a new service; stockpile thy grain, timber, flesh-meat and all tradeable commodities, for such may be necessary-required, in great and bountiful quantities, should his Highest-Highness approach thy realm. Otherwise and also, be prepared to quit any place, assemble thy servant-people wheresoever thou art commanded to go or surrender whatsoever is demanded of thee.

Only one warning shall be given-delivered, no more. If that is not obeyed, and the demands made therein not swift-summarily satisfied, then a final and terrible doom will befall thy home-realm. Every living creature will perish die, and the corruption so sown will hold that place in its deathly grip for many decades. If thou foolishly think to send-march an army against us, know that, howsoever mighty, it will perish-die in little more than an instant when the bombard’s doom is quick and easily brought to bear upon it. And if thou think to send spies, saboteurs or assassins against us, know and understand that there is no possibility of penetrating the legion of steel-armed, sharp-eyed, acute-eared warriors who always and ever guard both the doom-bombard and his Highness.

The sole action that will save thee and thine, will be immediately to obey-grant his Highness’ wish-demands. Yield unto him all and everything that he asks, and not one jot or tittle less, for then, and only then, will thou not suffer the cruellest and direst of consequences.

Furthermore, His Great Mightiness demands of thee right now, this very moment, that thou deliver-bring the maestro Angelo da Leoni to Trantio and yield him unto our custody. Satisfy this, our immediate and first demand, and we shall not today approach thy city-realm, but instead choose-find another victim for our inevitable and unavoidable infliction of doom.

There is no time to delay or dawdle. Act now, work quick, obey promptly, and when any and all of our demands are made, make haste, or bear the blame for a great annihilation.”

The shock throughout the gathered company was palpable. Bernado gave them a few more moments to allow the situation to sink in.

“We know they are capable of such destruction,” he said quietly, for the cloister was so silent there was no need to raise his voice any louder. Turning to the old priest, he said, “Father Benvenuto?”

“Indeed, your holiness,” answered the priest. “It has been confirmed that although they failed to lob their grenado into the city of Campogrotta itself, its explosion was sufficiently large and forceful to kill, almost to a man, all those within two thousand braccia, including several entire regiments of men and dwarfs, then tainted the land thoroughly for a mile further out, so that nothing could grow there, nor could anyone even step upon the ground for more than an hour without suffering sickness and in some cases death.”

“Now this letter claims they have more such bombards,” said the arch-lector, somewhat needlessly. “And that they will use them against us if we do not bow to their demands.”

Still, no-one spoke. The arch-lector looked at each of them in turn.

“Well,” he asked. “What say you? What is our best course of action?”

The Mercopian high priest, Flavio Tognazzi, took a sudden gulp of breath, then spoke,

“They clearly demand goods and commodities. Perhaps we could make a stockpile of such things, sufficiently large enough to satisfy their expectations, even if only to delay them, thus buying time for relief to come from allies. The realm’s merchants could be asked for a voluntary donation of old stock and surplus commodities, sprinkled with smattering of goods of fine quality. Such would go against our Mercopian strictures for fair dealing, but it is entirely permissible when paying a ransom to those who would do us so great a harm. Perhaps this way we might fool them? I mean to say, do such vile creatures even know the true worth of things?”

It was the Myrmiddian arch-priest Luccino De Sicca who answered,

“Not only will they surely know gold when they see it, but they are ingeniously cunning engineers and will likely have a full understanding of worth, weight and measure. Such tricks might fool goblinkind, but not ratmen. Besides, even if they were like goblins, their bellies would tell them soon enough if we failed to feed them as they demanded.”

Father Benvenuto raised his hand to draw attention.

“If I may say, your holiness, the letter does not merely ask for payment, but, and I think these were the words: ‘whatsoever is demanded’. They could command anything – ordering us to leave Remas, or to have our soldiers lay down their arms. They might offer enslavement in exchange for our lives and think themselves generous in so doing. Their kind have long used slaves of every race for their wicked ends, and so cruel is their mastery, so heinous the demands they make of mortal captives, they work those slaves to death.”

“Well,” said the arch-lector, “here they have already made one demand – that we deliver up the maestro to them.”

“That is preposterous, your holiness” sputtered Tognazzi. “They demand one man and in return will spare our city! What could they possibly gain from one man?”

“We cannot know,” said Bernado. “Perhaps the maestro possesses some secret they wish to learn, or is master of some arcane art they wish their own engineers to acquire. He most recently fashioned the steam engine and lightning cannon, both of which we know they also employ in their armies. They might wish to improve their own designs?”

“They may simply intend to squeeze every drop of ingenuity from him,” said Father Benvenuto.

“If I may speak, your holiness,” said Brother Duarte as he ran his finger down the parchment to a certain spot. “They do not offer to spare the city, as his grace, Father Flavio suggested, only that if we deliver the maestro that they shall not today approach.”

“Well saidm, brother,” said Father Benvenuto. “There is nothing to suggest they will not return later with further demands. Why would they stipulate all the particulars of our future submission if they did not intend to take more? If the maestro was all they wanted they would make that demand alone.”

“It matters not what they demand in particular, nor when or upon what exact terms,” said the Myrmidian De Sicca. “Whatever we yield, by doing so we reveal their power over us. They will then, by their nature, want more. Their ambition knows no bounds, they would steal everything in the world if they could, and they despise all other creatures. Any deal they make, any agreement they propose, is simply a step to some greater goal, some further theft, some future cruel conquest. In the end, all who deal with them come to ruin.”

He was careful not to look at the arch-lector Bernado as he made this point, for all present and indeed all in Tilea knew of the generally supposed treachery of his antecedent Frederigo Ordini, who (although never formally tried and proven to be guilty, only later declared so) was believed to have agreed an alliance with an uomini ratto faction that led to the annihilation of an entire Reman army in the swamps east of Miragliano.

“I cannot argue, your grace” said Bernado. “What you say is most likely. Yet, if we do not respond in some way, whether by yielding to them, or defeating them in battle, or merely luring them elsewhere, we risk our people suffering the same fate as the army at Campogrotta. It is said that only three men came away alive from that field of battle, and many more suffered and died from merely being in its vicinity. The rats’ capabilities are proven fact, despite any or all of their words likely being lies. And history proves that when they go to war they can field hordes of vermin warriors. Now, they have terror engines too.”

He turned to the two captains present. “This is why I have asked you here, Captain Ricci, Captain Lito. I would hear what you suggest regarding the military responses open to us.”

Captain Ricci had yet to be elevated officially to generalship since the death of Captain-General Scaringella on the Via Diocleta. It had been widely presumed that the promotion would go to Captain Soldatovya instead, when he returned from the war against the vampires, but he never did. Ricci was, nevertheless, despite his lesser rank, now the military commander of the army of Remas.

“Your holiness,” began the captain. “Much depends on what course you wish me to pursue. If we yield to their first demand, then it might buy us time to prepare for a defence.”

“Captain,” interrupted Tognazzi. “We cannot in good conscience hand over one of our greatest and most able citizens, innocent of any crime or treachery, and one who might well be the best instrument we have to employ against this threat. If anyone could devise a means to thwart this terrible engine by anything other than brute force, without the death of hundreds of soldiers, it would be him.”

“Your grace,” answered the captain, “it is not for me to decide the maestro’s fate. But even if we choose not to give the maestro to them, we could still buy time by simply promising to do so. Either way, there seem to me several possible strategies open to us, each of debatable efficacy. We might ask for relief from another state, to join us on the field of battle, so that the force dispatched against the foe is sufficient to the task. But who can we ask? And will they oblige us? Will they send sufficient strength? How quickly can their army reach us? And how might they avoid interception by the foe upon their march? Also, either hand in hand with forming such an alliance or not, how might we effectively prevent the enemy from approaching the city? By ruse or military action? Can we distract them, lure them away? Or, despite their claims of legions of guards, can we destroy their engines through sabotage? I can say that although our army has grown stronger since the losses on the Via Diocleta, and indeed gained the most welcome addition of the Cavalieri Benedetti, it has not yet regained the strength it had three years ago.

“Also, we only know that they once employed such a grenado, and that they have now sent a letter claiming to have more; claiming to have an army. Surely, before we bow even to the pettiest of their demands, and certainly before sending such as the maestro to them, we should at least ascertain their strength, their whereabouts and crucially, whether they do have another bombard.”

“Wisely said,” declared the arch-priest of the church of Myrmidia. “Know thine enemy: his strengths and weaknesses, his disposition, his goals. None of these things can be ascertained from a lying enemy’s boastful and threatening letter.”

“’Then,” said Bernado, “As I see it, we thus have three tasks. Captain Ricci, learn what you can of the enemy force. Captain Lito, I command you to find out all you can about their engine.”

The young artillerist looked troubled.

“Is this something you’re afraid to do?” asked Bernado.

“No, your holiness. But would not the maestro be a better choice to ascertain the true nature of such a novelty as this bombard?”

“He might well be, but I think you can understand why he was not invited to this council,” explained Bernado. “Besides, we already know from Campogrotta the destruction they are capable of. You must discover the bombard’s whereabouts, its size, how it is moved, and how fast. I am sure you are just as capable of learning these things as the maestro.”

The captain gave a nod. “As you wish, your holiness.”

“Meanwhile,” said Bernado, “the rest of us must decide how exactly we will respond, should the enemy’s claims prove true.”

“Your holiness,” asked Father Benvenuto, “are we to include accepting their terms, giving them the maestro, and later whatsoever they demand, as options in our deliberations?”

“If that proves to be the only option left to us to prevent the destruction of the city and the massacre of its population, then our hand may well be forced!”

………………………………………………………………………………………………….

The Battle of Palomtrina, Part One: Make Ready!

Palomtrina, Winter IC 2404-5

For several days and nights, Arch-Lector Bernado Ugolini had agonised over how to deal with the new and fearful threat. Of course, he had mustered the army immediately the danger was known, and had ordered it to march as soon as possible – it was undebatable that the enemy could not be allowed to approach the city. They possessed a terror weapon the likes of which, until its power was demonstrated at Campogrotta, was unknown in history …

… except, perhaps in ancient, primeval times when the gods themselves visited their destructions on the world. This new weapon could obliterate a city, or an army, or both (if the army were within the city).

After deciding he could not risk the destruction of any Reman settlement, nor could he yield to the enemy’s blackmail demands (for that would certainly entail further such demands and the eventual ruin of the realm), he marched the army directly towards the foe. Then, having been advised that to ensconce themselves in earthwork defences would simply allow the enemy to bring the terror weapon to bear upon them, he accepted that he must keep moving and face the foe in the field, as far from any settlement as possible. So it was, that as soon as the enemy force was espied, the Reman army deployed on the western hills of a valley several leagues east of Palomtrina.

The maestro, Angelo da Leoni, had convinced his holiness Bernado that they could not risk shooting at the terror weapon, for the damage so done might cause a cataclysmic explosion which would annihilate every living thing on the field of battle (as had likely happened at Campogrotta). Consequently, the army contained some rather some unusual and irregular elements, hastily raised, in the form of several dock-worker ogres armed with instruments for pushing the weapon over and wrecking its traction engine …

… and a volunteer force of citizen strong-men as a second ‘smashing crew’!

By means of one or both of these companies, it was hoped the terror weapon could be halted and disabled, without loosing its deadly grenado.

Otherwise, the Reman force was composed of the realm’s marching army, and the standing force of Palomtrina, the latter being a company of well-drilled handgunners clothed in the colours of Remas.

Bernado himself rode with his herald, Fazzio and his secretary, Brother Duarte, and as the army deployed, he positioned himself close to the centre of the lines, directly behind the Palomtrinans.

From there he watched, anxiously, as the foe deployed. Surprised to see that they possessed so many engines of war, he then assumed that this ‘Seer-Lord’ Urlak had a proclivity for such weapons, likely culminating in the development of the monstrosity which the enemy called its ‘doom-bombard’.

He was also surprised to see how few warriors they had – not that there was an absence of large regiments, but rather that he had expected many more, a veritable horde. Perhaps their need to conquer, then garrison, both Ravola and Campogrotta, had stripped them of their traditional numbers?

Most of the vermin-warriors were massed upon the enemy’s right, in the form of three, large, regimented bodies.

The right-most regiment were clad in yellow rags and iron armour, the front rank of which hosted several unusual looking specimens, one in flowing robes and sporting a bloatedly tall hood, the other bearing an unwieldly profusion of sparkling blades.

To their immediate right was a company of brute-rats, one of which carried a palanquin, upon which rode a banner bearing, armoured chieftain.

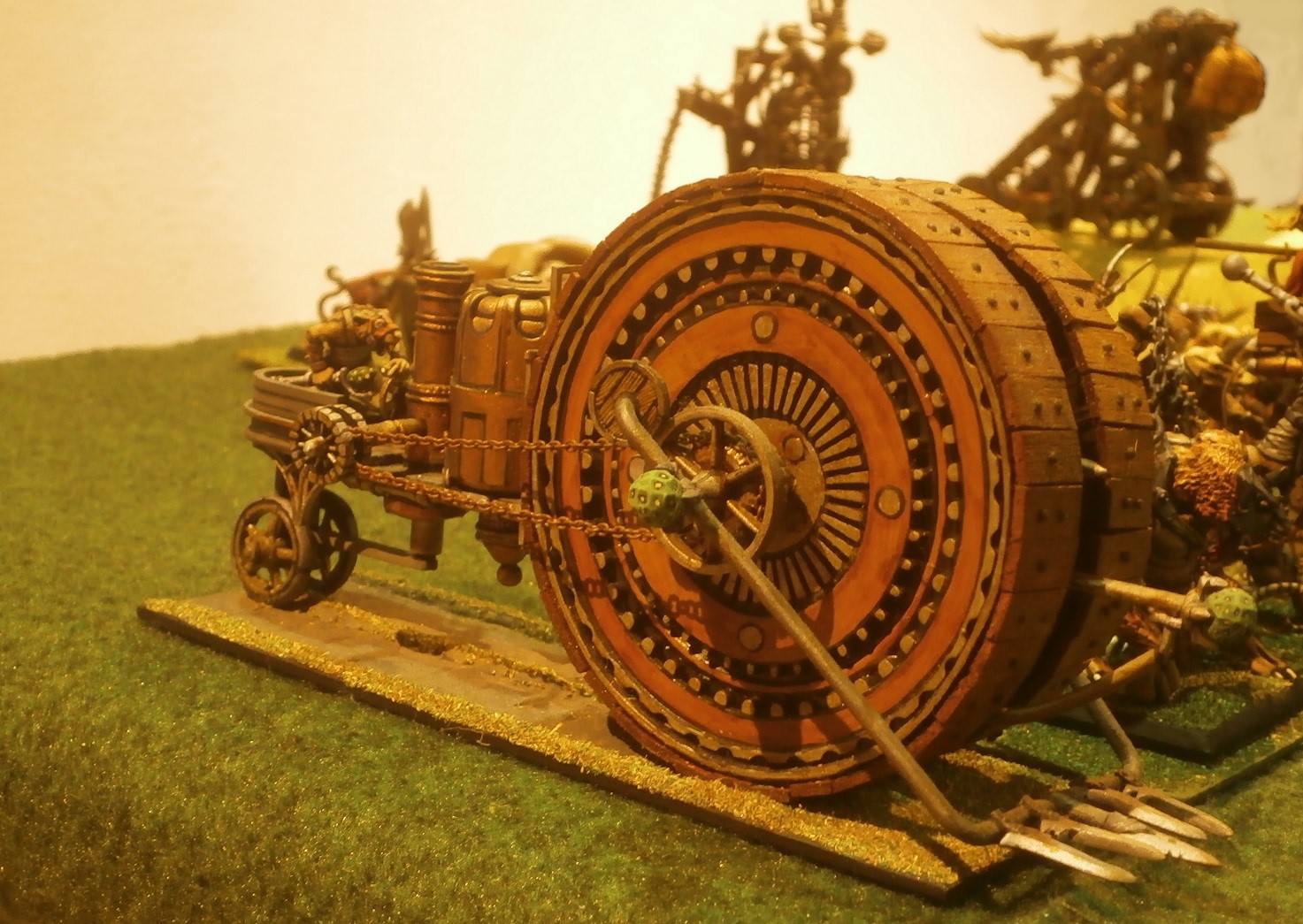

Out on the far-right flank trundled a giant, wheeled engine of considerable complexity.

Bernado wondered whether the maestro had spotted the same. Any engineer of an enquiring mind would undoubtedly find such a machine as fascinating as it was terrifying, probably more so!

Behind the yellow-liveried regiment was a collection of wagons and oxen, being the enemy’s baggage train. This included a tall, flimsy and rather odd-looking contraption, which was unlikely to be a weapon, for then surely it would be part of the line of battle, but rather something else entirely.

Bernado now recalled something like it being mentioned in the reports from his army’s scouts, trundling a little apart from the main force. When he had asked the maestro’s opinion, the genius had simply answered that without looking upon the machine himself he could not offer any suggestions as to its purpose. What with da Leoni tending the cannons on the hill, it was doubtful that he could see it now.

He was surprised to see that the doom-bombard was not amongst the baggage where he had expected it to be.

To the yellow regiment’s left were a skirmishing mob of leather robed ratmen, sporting what appeared to be brass kettles of some kind upon their backs, connected to their face masks by leather tubes. They carried brass globes in their clawed hands, which Bernado assumed were grenadoes of some kind.

Behind the grenadiers, mounted atop a small hill, was a catapult …

… its leather robed and hooded crew skittering about on flimsy platforms, preparing it to lob whatever it was it lobbed.

Further towards the enemy’s centre marched the largest enemy regiment, carrying two banners: one a filthy rag adorned with skulls and shards of iron, the other a yellow sheet daubed with the uomini ratto’s most common emblem.

The warriors themselves were garbed in red and carried heavy bladed spears. Perhaps imagined, Bernado seemed to hear their chittering as they dressed their ranks and files.

Closer still to the centre came the third large body of ratmen, each and every one of whom was entirely enveloped in robes and masks of leather.

Their presence confused Bernado, for although three massive engines – warp-lightning cannons – trundled beside them, the doom-bombard was not one of them. By their garb he presumed these warriors to be what the scouts had called the ‘engine guard’, always reported to be escorting the terror weapon. Yet here they marched as a fighting regiment in the line, their heavy robes surely now an unnecessary encumbrance?

Behind them, arrayed upon the central hill, was a line of extraordinarily long-barrelled handgunners, two to each piece, with triangular pavaises set in front of each of them, dually employed as rests.

Bernado could only suppose that such extended barrels meant a greater range than ordinary handgunners, and perhaps more powerful shots?

Next in line, came three more of the enemy’s engines, the cannons.

Bernado recognised these, for they had long been employed by the uomini ratto. Unlike his own artillery pieces, they fired not round-shot but burning streaks of lightning. At least one, perhaps two, seemed to be steam-powered, needing no draught animals or slaves, like the maestro’s steam tank.

Beyond the three cannons, above and behind a swarm of rats, and on top of another rise in the ground, was a pack of giant rats …

… being whipped into subservience by several ratmen at the rear.

Further out was a massive mob of slaves, the only metal evident upon them being that of their heavy blades and the manacles at their wrists.

Among those at the fore were what he presumed to be three commanders, one with a cleaver-like blade and hooked-hand held dramatically aloft, another waving a pistol of strange design.

And there, behind the mob, upon the far flank of the enemy’s line, was the terror weapon, unmistakeable with its huge pair of bombard barrels aiming perpendicularly upwards.

‘Why put it there, where it is less protected?’ Bernado asked himself. ‘And why is its guard regiment elsewhere in the line?’

Then it occurred to him that the answer could be simple. It was still protected, but by the most expendable bodies – the slaves and the pack-rats. Perhaps the foe believed that he and his soldiers would think it madness to approach it at all, considering the potential instability of the grenado it carried? And yet to leave it entirely unprotected was not an option, which was why the scum of their army was given that duty.

Annoyingly, he knew the dockyard ogres with their pushing poles were on the wrong flank of his army, but thankfully the smashing crew of burly citizen volunteers was not! Hopefully, they could get to the engine and topple it. And by Morr’s grace, he earnestly hoped that in so doing they would merely immobilize it, and not cause it to explode!

“Pray with me,” he instructed Duarte. “The prayer for protection in battle.”

The two of them then intoned together:

“Sancte Morr, defende nos in proelio, contra nequitiam et insidias hostium esto praesidium.”

…

Urlak surveyed the enemy before him, a little dismayed to see their numbers. He had been led to believe their army was weak after its wars against both ogres and vampires, but what now stood against him did not seem so. He and his masters had worked for many years to foment those wars, hatching a complex series of schemes involving umpteen agents, vast bribes and assassinations. Once this battle was won, he would have to recall who exactly had reported the weakness, and have them flayed.

He was even more concerned that the enemy had chosen to fight. He had fully expected, considering what he had done to Campogrotta, that the Remans would plead for mercy and yield whatever he demanded. Yet here they were, in strength, prepared to take the field against him and his doom-bombard.

Perhaps there was a traitor in his army who had passed word to the foe? Perhaps instead Clan Skryre had tricked him and were colluding with the Remans? But no, as his runners came to report the shape of the enemy’s deployment, he knew they were taking the threat seriously, for not only had they arrayed their very best warriors against the engine, there were also elements in their force that indicated an earnest intention to disable it.

Before his eyes, for example, striding among the enemy’s left wing, was a body of oddly armed brutes, for they carried not blades but a brace of long poles terminating in wooden blocks and a huge iron bound club. He had wit enough to realise exactly what they intended to do – to topple the bombard, surely?

More fool them, then, for arriving on the wrong flank, so far from the engine. Unless, he wondered, there was another such body on the enemy’s right flank? Perhaps more ogres, or some other means of disabling it? He could just make out their artillery on that side – a brace of brass-barrelled, heavy cannons atop a hill.

Perhaps those guns intended to fire upon bombard? Yet, he could see their muzzles were currently angled towards the middle of his army.

It seemed most likely that foe would be somewhat trepidatious when it came to the bombard’s destruction. If the maestro was with them, then surely such as he, having learned of the explosion at Campogrotta, would deduce the danger inherent in employing any form of shattering impact against such a bombard?

‘Idiot fool!’ thought Urlak, his lips curling in contempt. ‘He knows nothing.’

Indeed, he now wondered why Clan Skryre wanted the maestro so much, if the man-thing was too stupid to see what was truly what.

His servants described the enemy’s right flank. Furthermost out came the heavily armoured horsemen, the newly formed Knights of Morr, the Cavalieri Benedetti, which he had earlier received reports about.

These were meant to be among the finest men-at-arms not just in Remas, or Tilea, but the whole of the western world. Proven warriors who had sworn vows to serve the men-things’ god of death in their latter years, before their strength waned. If the likes of them had been deployed against the bombard, then the foe surely was taking the threat seriously?

‘Let them become caught-entangled in a swamp-mire of slave-scum,’ he cackled to himself.

It did, however, occur to him that the knights might be there quite by accident – after all, the ogres with their pushing poles had been badly misdeployed.

Apparently, there was a body of burly men-things beside the mounted knights, lacking soldiers’ arms and armour. Perhaps, he thought, the enemy’s numbers are only so large because they have dragged every fit and able manthing from their city, not just their soldiers?

They had skirmishing swordsmen on that flank too, apparently led by a cloth-clad priest.

He sniggered when he heard this, for what prayers could be used against such cunning as his, against such lies as he was able to weave? Still, bullets and bolts would surely sting, and the enemy had no shortage of them. Not only did they have a large regiment of handgunners in their midst …

… they had crossbowmen galore. Indeed, so many that behind a large company of dwarfen crossbows …

… atop a rise, there was a body of Condotta crossbows able to launch their bolts right over the dwarfs’ heads.

And before his own eyes, he could see more crossbowmen atop another little hill, the famous Cathayan mercenaries by the look of them …

… these able to shoot over the small company of pistoliers trotting up below them.

And, of course, there was the brace of heavy guns, able to fire upon almost every part of the valley.

Urlak knew only too well what such pieces could do to massed ranks. Annoyingly, he also knew that their positioning just beyond the crest of a slope would only make it more difficult for his warplightning cannons to disable them.

Seer-Lord Urlak could see the enemy’s main fighting strength very clearly, for they were to the left of the centre and thus almost immediately before him.

There was another Cathayan regiment, bearing polearms of an unusual kind rather than crossbows like their kin on the hill.

Their standard bore one of Morr’s keys, so they had likely been a long time in Reman service. Unlike most of the other regiments in the enemy’s army, rather than drums they carried horns, the blaring of which sounded pathetic to Urlak’s ears!

A gorgeously liveried regiment of foot-soldiers bore not only their own colours but what was likely the army standard. They bore great swords at the fore, and halberds at the rear.

A swaggering, plate-armoured captain commanded them, and even from a distance Urlak believed he could make out fear on the man’s face. Perhaps the fellow was remembering what he had heard about Campogrotta and so contemplating the horror that could engulf the entire valley?

‘Another fool,’ thought Urlak, his eyes narrowing with glee. ‘I have made fools of them all!’

Well done Padre! You’re campaign is unbelievable, and seeing the powerful forced to deal with such a dreadful threat is fascinating. The way you’ve written this, risking both great and small, and creating a story from the decisions of the participants in your great campaign, giving the characters a real degree of agency, salted with the vagaries of genuine chance that the dice bestow us lends this a veracity that is downright rare in fiction. Well done indeed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I honestly feel like I am being ‘carried along’ by the campaign, which of course I am. All I have to do is turn the events into stories.

LikeLike

There’s some truth to that, but it takes real skill to make good stories out of it, and you make great stories. This doubtless inspires your players and makes the campaign better, too. 🙂

LikeLike