Fleshmeat

Spring 2402, The Via Nano, south of Tettoverde Forest, Eastern Tilea

His goblins emerged from the trees, scuttling over the rocks in their usual, higgledy-piggledy manner. Habbdok did not bother to count them, as he could see there were still plenty enough left for his purposes, which was all that mattered to him. Most men who saw his servants laughed. One captain in the Princes described them as ‘funny little things’. Knowing them – their nastiness, their unpleasant stench (even to an ogre’s resilient nose), their foul ways (and it takes considerable talent to appear foul to an ogre) – Habbdok could not see what the man had meant. Annoying, yes. Too small and skinny for both their arms and armour, yes. Funny, no. Not in the slightest.

As they clattered to a halt, Habbdok squinted, flicking his eyes from one to another in search of any particular one he could expect to get some sense from. The closest to him was so out of breath he looked as if he could not speak if he tried. All his own fault, of course, for he wore a triple-layered helm tilting to one side and an ill-fitting iron breastplate, all made heavier by several, dangling lengths of chain with no apparent purpose. His cheeks were puffed, and he all but dragged a battered and most likely blunted iron axe with both hands, his back and legs bent from the strain.

There was a clutch of four goblins off to one side, even more misshapen and bent than the puffing one. They simply stared at Habdock as if they were expecting him to speak. Habbdok could feel the usual surge of furious impatience already building, his head throbbing beneath his skull plate, as he marvelled yet again at their stupidity. They were here to report to him, yet they seemed to expect him to report to them!

Still they stared.

Just as he was tempted to stick the razor-sharp tip of his hunting bolt through the panting pie-hole of the foremost goblin, he caught sight of a little runt with ridiculously over-large horns adorning his noddle-pot, and not a single tooth to line his raggedy maw.

That one, he did recognise. He remembered that one had proved capable of something approaching intelligence in the past. ‘Horny’ was the name Habbdok had given him before. Of course, he had no idea at all what the goblin called himself, and he certainly did not care.

Habdock pointed a crooked finger at the goblin. Horny took the cue, and himself pointed towards the forest canopy.

“Mighty Hunter, lord of gristle and bone, we’s been over there an’ all ‘round an’ back agin,” he said.

“Very nice,” snarled Habbdok. “Stretching your legs and ‘aving a breath of fresh, eh?”

Horny grinned to reveal swollen, bloody red gums.

“An’ lookin’, o’course. A lot o’ lookin’.”

“So here’s a thought for you,” said Habbdok. “Why not tell me what you saw before I get so angry you’ll never have a chance to tell anything ever again? Did you see the … the … forest people, or not?”

Almost imperceptibly, the goblin’s grin changed to a rather more fixed affair. Habbdok failed entirely to notice any difference, having never been of a mind to consider such subtleties in runts like this.

“No peeps. Nuffink,” said Horny. “If they’s there, then they’s slippery an’ sneaky, leavin’ not so much as a bent leaf or a toe print behind.”

Habbdok pondered this. If there was no-one there, then why had Mangler ordered the army to go the long way around? Mangler had clearly planned, at first, to march right through the forest, but then he had changed his mind, never explaining why. Most of the lads seemed to think it was because what little they might find in the forest would not make up for the effort of finding it, what with branches, roots and thorny things forever getting in the way. One or two had suggested – never within earshot of Mangler or any of his lieutenants – that Mangler was afraid of the trees and what they contained, conjuring thoughts of bark-skinned, monstrous demons and invisible foes planting arrows into your eyes, just like in the old stories of the forest. Habbdok had given this latter suggestion little credence, yet still wondered why they couldn’t penetrate the forest just little, if only to find some bigger cuts of fleshmeat for the supper pots, like deer or goats, or maybe even some sweet elven flesh? And as the trees at the edge were not too densely packed, surely it would save time to take at least some forest path short cuts, rather than continue this lengthy circumnavigation?

Then again, he admitted, there could be good reasons for their choice of route, including the likely possibility that Mangler intended to enjoy some good looting from Tilean settlements ‘off to the side’ as they made their way. Having a destination in mind was one thing, but there were usually plenty of opportunities that warranted taking one’s time getting there. And none of the lads were complaining about taking the easy route: the rootless route; the flat ease of the old road instead of the tangled briars of the ancient forest. It was just a pity that the wild animals Habbdok would dearly love to hunt (then gorge upon with relish) were so unlikely to favour the same route. Nor were the delicately flavoured Sylvan folk the sort to traverse such an open road. He had only once tasted of their flesh, and that salted and aged, but he had heard more than one report that when fresh it was delicious beyond compare.

While Habbdok the Hunter did his pondering, two of the goblins were sharing their own thoughts.

“He’ll ‘ave us running back in any moment,” said Frokit Anglegrinch, both hands clutching the shaft of his bill-hook as if he might fall without it. “Look at ‘em,” he said, indicating the ogres streaming past behind Habbdok. “Everyone of them gets to walk – I’d go so far as to say amble – while we has to scamper never-ending hither and thither through a tangle of thorny spikes.”

His companion, Pooshin Cotchwallop, twisted his frowning mouth to even lower depths, his chin thrusting more prominently between the sagging lips. If one took into account his protruding eyes and his boiled potato nose, neatly framed by his chainmail hood, the sum of the parts made a very ugly whole. Mind you, Frokit was no looker either.

Pooshin peered beyond the Ogre hunter at the marching column on the road.

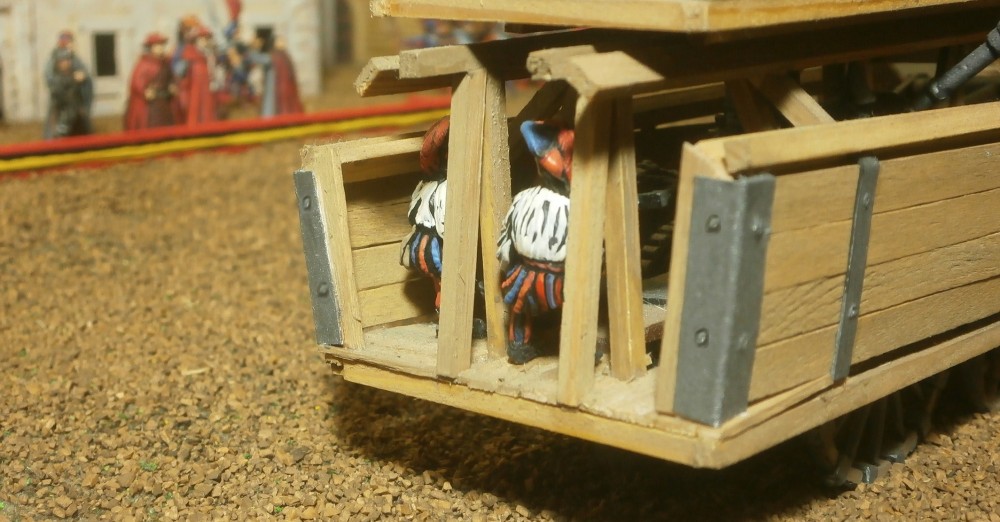

“Some ain’t even doing that, Frokit,” he said, watching the huge, grey beast carrying the scraplauncher and its numerous goblin crew. “Look at them lucky sods, sitting all comfy-like as their beast does the work beneath their idle arses.”

“I hopes they get splinters in their backsides,” Frokit spat through his teeth, “and all the jolting gives their joints the jip.”

At last, Habbdok had come to a decision. Clearing his throat loudly enough to make the beast of burden behind him grunt …

… he gave his orders:

“Right! You’re all going back in, an’ this time you’ll look properly, or I’ll have your eyes in a bowl for a tasty treat while supper roasts. Everyone knows what lives in these woods, and if you can’t find them then you’re not looking hard enough. Do something naughty to get their attention. I know you’re good at running away. See if you can’t get them to chase you. If you can’t net ’em yourselves, bring ’em my way and I’ll stick a stick through ‘em.”

Behind him the column continued its journey …

… Mangler the Merciless’s Mercenaries, flags a-fluttering overhead while their iron shod boots ground the old road to dust.

To see modelling articles on the scraplauncher and the ogre hunter, go to Ogres,

Part 1.

——

All Much of a Muchness

The Reman Town of Stiani, Spring 2402

Baccio had been watching the door to the other room for a while now, awaiting his friend’s return.

This was not his customary habit – usually he would get on with drinking without a care for his friend’s absence. But, considering their current situation, there was a genuine chance his friend would not return, and that would leave Baccio entirely alone in the world. He had attempted to distract himself by listening to the inn’s landlord talking loudly with some local fellow – exactly as Ottaviano had suggested he did.

Then when they shut up, he had brooded in silence, eyes fixed upon said door. Relief flooded through him when, at long last, Ottaviano burst through it to take his place back at the table.

“Not good,” said Ottaviano. He gestured to the little company of men he had left feasting in the next room. “They are Verezzan merchants, and they are returning from Trantio.”

“Well, that’s what we wanted,” interrupted Baccio. “News from Trantio. Or were they tight lipped?”

“Oh they talked alright. What I mean is that they didn’t have anything good to say. ‘Til now we’ve been at best defeated soldiers, at worst cowardly mercenaries. But now, we’re apparently murderers too.”

“What? Why? We were paid to fight and we fought, even against the odds. That should stand us in good stead.”

“The story they told me happened after the battles and the fall of Trantio. They said some of our lads have killed a Morrite priest. And not some lowly father, either, but an emissary of the arch-lector himself, carrying a message for the dead prince.”

“Why carry a message for a dead prince?” asked Baccio, confused. Then his faced took on a look of horror. “You mean … Girenzo is a vampire?”

Ottaviano shook his head. “No, you fool! Of course not. The message was sent when Girenzo was alive. It just didn’t get to him in time.”

“Oh,” said Baccio, sounding reassured. “Still, it doesn’t sound right. Why would any of our lads kill a priest? Especially a Reman one, when Remas is one of the few places left we can go?”

Ottaviano shrugged. “I honestly don’t know. And no-one ever will, because the lads in question were caught and killed by the Duke’s men. No trial, no questions. Dead.”

“Well the last part doesn’t surprise me. The Pavonans are killing everyone who fought against them, no mercy given.”

“They were killing everyone,” corrected Ottaviano, “but not now. The merchants said that Bucci’s crossbow company have been offered a Pavonan contract to remain as part of the garrison in Trantio. ‘Needs must’, it seems. Now that his newly enlarged empire happens to sit so close to the undead, Duke Guidobaldo wants all the soldiers he can get, even ex-Compagnia men.”

“Well, that’ll be it then. The Duke wouldn’t want to anger the arch-lector, not when everyone needs to stand together against the vampires – and so he had the priest killers executed.”

“Except the story doesn’t make sense. You yourself said so. Why would any Compagnia lads do such a thing?”

Baccio frowned, then sighed. “Maybe they didn’t know who he was? Maybe the priest was in disguise? Or he threatened to tell the Pavonans where they were?”

“Could be. Whatever the reason, it doesn’t help those of us still on the run. No-one likes priest killers, especially when Tilea needs all the holy men of Morr it can get.”

“So,” said Baccio, “we don’t tell anyone who we are … I mean, who we were. It’s worked well so far.”

The two of them had indeed found it remarkably easy to gain free passage, by the simple expedient of telling any who asked that they were off to join the arch-lector’s crusade. People did not then merely let them pass, but fussed to find them provisions and beds, and to see them on the right path. ‘All roads lead to Remas’, was the saying. Right now, it was true.

They ordered another jug of wine, more bread and cheese, then ate silently for some time. They were hungry. It was Baccio who finally piped up.

“What else did they say about Trantio?”

Ottaviano talked in between stuffing chunks of bread in his mouth. “Martial law … bad for trade. Duke Guidobaldo setting all the prices … His army’s still in the city, not sacking the place, but eating everyone out of house and home.” He drank a deep draught of wine. “And the Duke’s got elves in his service now. Riders on white horses. He might not like dwarfs, but he doesn’t seem to have a problem with elves.”

“Maybe it’s beards he doesn’t like?” quipped Baccio. “I heard the arch-lector will excommunicate him for continuing the war.”

“I don’t think that’s way the duke sees things. He calls himself Morr’s ‘most obedient’ servant, and claims all he has done was so he can more certainly defeat the undead.”

“You said as much in summer, didn’t you? How he would be the hero when the time came.”

“I did,” said Ottaviano, rolling his eyes. “I just didn’t expect it all to work out so well for him.”

“Apart from the death of his son.”

“Aye, apart from that. Apparently not one for grieving though. The merchants said his son’s corpse, still warm, was packed off to Pavona in a cart …

… while he simply commanded his other son to come and serve in his brother’s place. He’s going to give the city to the lad – a mere boy!”

“In name he might. But in truth it’ll be him that rules.”

“Aye,” agreed Ottaviano. “I think that man wants to rule all Tilea. I think he wants to be a king – they’re even calling it the ‘War of the Princes’. But I counted only one real prince.”

“Dukes, princes, lords – they’re all much of a muchness to me. And arch-lectors too.” Baccio snorted, then looked his friend in the eye. “Are we really going to join this crusade?”

“Well, we are going to Remas, even if it’s just to make sure we don’t end up in Pavonan hands. Let’s see what happens when we get there, eh? Might be preferable to spend a while labouring on defences or such like. That way no one will suppose us to be mercenaries and start asking where we came from.”

“The Remans won’t care if we were Compagnia men, surely?”

“No,” said Ottaviano, “I doubt they will. Could be the opposite – they might like us all the more for being soldiers. Remans like mercenaries. Their army is made of mercenaries, by law.”

Baccio raised his hand to hush his friend, a smug look of cleverness coming over him.

“It was,” he said, “but no longer. Now they say … at least the landlord said to one of his neighbours before you came back, that the arch-lector is raising Remans to serve him as citizen soldiers. Maybe he wants to emulate Duke Guidobaldo’s successes with his Pavonan fanatics?”

Ottaviano gave a fake laugh. “The arch-lector just wants soldiers, and all he can get. He’s already threatened to excommunicate everyone who in any way hinders the crusade. He’s even asked the wizard lord of Campogrotta to send his Ogres. He means business. This crusade is going to be big.”

“That lad in Palomtrina said elves from Tettoverde forest were joining the crusade,” added Baccio.

Ottaviano laughed loudly. “That lad in Palomtrina told us that painted ratmen were swarming on the western coast, and that flying arabyans had captured Luccini while the young prince, who was actually a girl, cried. I wouldn’t put too much stock in what he said.”

“Maybe not. But I’m not so sure the crusade is going to be so big. They say the arch-lector won’t send help to Urbimo.”

“Huh?” asked Ottaviano. “Why?”

“That’s what the landlord’s neighbour was complaining about – he has family there and the arch-lector has sent no help at all.

The man said his holiness is only really concerned about Remas’ safety, not that of the rest of Tilea. Calictus hasn’t even recognised the hero of Pontremola, neither rewarded him, honoured him nor even invited him to attend his court, because that would mean acknowledging the Viadazan crusaders were forced to fight alone, and lose their city in so doing.”

Ottaviano rolled his eyes. “Nonsense. That’s just gossip and tittle tattle. If the arch-lector was so embarrassed by the fall of Viadaza, why has he lodged its exiled lector in his palace? And only a fool would think he could defend Remas while all the rest of Tilea fell to the undead.”

Baccio grinned. “So, the landlord’s neighbour is an idiot. But it’s good to know what people are saying. Did you ask the Verezzans about Raverno? Raverno is close to their own city, so they should know what’s going on there.”

“I did, and they do,” said Ottaviano. The two of them had talked previously about going south not west, maybe to Verezzo, or maybe Raverno. As there was no love lost between Pavona and Verezzo, however, this meant it could well be Duke Guidobaldo’s next conquest in his desire to forge a mighty empire. Neither men were keen on fighting the Pavonans again so soon, which left Raverno looking like the best choice.

“There’s trouble of a different kind there,” Ottaviano continued. “Since Khurnag’s Waagh was defeated, the VMC northerners in Alcente have begun throwing their weight around, just like general Fortebraccio said they would. A VMC army has already held Raverno to ransom, claiming they were exacting revenge for the ‘defenestration of Raverno’ – the gods alone know what that is.

Apparently, they’ve burnt the settlements at Camponeffro south of the city, and extracted a large sum of gold from the terrified Ravernans. I doubt they’ll stop at that, nor honour whatever terms were agreed. The merchants said the VMC were little better than armed robbers, who call their threats ‘haggling’ and their plunder ‘profits’.”

Baccio shrugged his shoulders. “That sort of trouble could be good for us, maybe we should go there? It could mean work.”

“You’re still thinking like we’re part of the marching Compagnia. It’s just me and you now. I don’t want to go where we might find ourselves on the losing side, and with no friends left.”

“How is going to Remas better then? Fighting the undead is going to be one hell of a bad war. Wouldn’t you rather be paid to fight in a war between merchants rather than between the living and the dead? Maybe we should go to Estalia and join Captain Mazallini? …

… They still call themselves Compagnia del Sole, despite taking a separate contract. I reckon they’d take us on gladly. I knew the captain well, and I didn’t join in any of the nastiness when he left.”

“I don’t know,” said Ottaviano. “What if the seas are swarming with painted ratmen? Maybe it is best we join the crusade? Be more than mercenaries for once? Fight for more than money? We’ve never been anything else and look where it’s got us. If the undead defeat the crusade while we’re burning crops in Alcente, all we’ll have done is bought ourselves a little more time before they get to us. I’m not talking about duty, but common sense: We’d be fighting so that everyone might live, including us. That might be the only good choice left.”

“Nice speech. Stirring even,” said Baccio. “Meanwhile, in the real world …”

—-

A Need for Nightmares

Remas, Spring 2402

Standing by the window, Father Biagino could already hear the bell ringing faintly in the distance. It was sounding a little earlier than it had the day before. His friend and fellow Viadazan refugee, Father Antonio, who commanded the bell, must be intending to perform a wider circuit through the city streets today, and thus the early start.

On each successive occasion, Antonio’s procession had grown, as ever greater numbers joined the whipping and wailing, scourging their mortal flesh to purify themselves in holy Morr’s eyes, praying that the same bloody ritual might one day provoke a frenzied urge to fight the foe no matter how horrifying it was; no matter how monstrous or foul. And the birth of the flagellant cult was almost entirely due to Antonio’s incendiary street-corner sermons and powerfully ominous prayers.

He had stirred Remas from its gentle slumber into a waking nightmare, opening people’s eyes to the approaching danger, while the church’s highest clergymen, following the arch-lector’s dithering lead, seemed forever locked in vacillation, unable to decide exactly what should be done, nor how, when or where. The way things had been going, it had seemed likely that no Reman blade would be unsheathed until the undead legions were already scrabbling over the city walls.

Biagino could not fault Antonio’s ardour, nor deny the need for action. Yet he was not sure that raising another army of apprentices, peasants and ill-paid mercenaries was the best course. They had done exactly this at Viadaza …

… and had marched at the head of the rag-tag force so created. That army had pushed the enemy back, even brought down the vampire Duke Alessandro …

… yet it was still not enough, for while their backs were turned, Viadaza was lost, and the battered remnants of exhausted peasant crusaders could do nothing about it.

“Death begets death,” one old fellow had proclaimed after that battle of Pontremola, as they wandered aimlessly in Viadaza’s vicinity, bereft of any hopeful course of action. Biagino had not known exactly what the old fellow meant by this, but nevertheless he suspected it was true.

Here in Remas, Biagino thought, there was a chance to do things differently, better: to gain the backing of church and nobles as well as the common people, and thereby forge a professional army, able to feed itself, march and fight. Then march and fight again, and again, until victory was won. This time they should learn all they could of the enemy, plan and prepare for all possible contingencies, ensure that their lines were secured, the towns and cities adequately garrisoned, the army properly armed. If Father Antonio had his way, however, he would surely once again lead a rabble from the city: unprepared, unsupported and ill-advised.

Biagino would rather such men were put to use effectively, doing what they were good at – digging earthwork defences, repairing crumbling walls, driving mules and carts to move supplies. Then the professional soldiers would be properly supported, and better able to concentrate on strategy, tactics and battle.

Dong!

The bell’s sombre tone was quite contrary to its size and placement.

If it were three times the size and housed in a great, stone tower rather than suspended from a wooden gibbet, then such a sound might indeed be expected. Biagino wondered whether some enchantment had been put upon it to make it ring with the note of a different bell, from another time and place.

That was no doubt the intention – as if it were the bell hanging at the gates of Morr’ s garden, tolling the receipt of each passing soul.

Estimating the bell to be at least two streets away, he turned back to the chamber just as the door opened to admit the man he had been waiting for.

Even if Biagino had not been told, he might have guessed the fellow was a fisherman, what with weather-beaten, leathery flesh clearly advertising years of hard labour in the wind and sun despite his middle age and a head of hair without a wisp of grey. Carlo Gora was his name, a Viadazan by birth, although now a refugee like every other living Viadazan.

Carlo closed the door then, by way of greeting, said only, “Father.”

Biagino noticed Carlo wore a fighting blade by his side, and a pack upon his back, which made him wonder if the man was intending to depart Remas. Or perhaps he just wanted to be ready to leave at any instant.

When Biagino gestured to the chair, Carlo failed to move.

“Please, do sit,” Biagino said. “I am not some great, noble-blooded churchman with a multitude of airs and graces. I’m merely another homeless wanderer like yourself.”

The fisherman seemed barely to register Biagino’s words, and instead of taking the seat, walked over to stand behind it, as if standing at a rail in a temple, to receive the incumbent’s blessing. His eyes were wide and seemed to be focusing on the space between the two of them, rather than the priest.

“Or stand, yes, if you prefer.”

Hearing a shout from the street, Biagino glanced through the window again. On the street below ran a sleeveless man, bald and with a band of iron fastened about his upper arm. As he pelted down the street, howling, he spun the most vicious iron flail above him, consisting of not one but two barbed weights. Perhaps, thought the priest, he had shaved his head to avoid a nasty accident should his hair become entangled?

A flagellant, off the find the bell no doubt. Hopefully, once he got there, the man would have the sense not to attempt flagellation with his heavy flail, as it was surely much better at killing foes than purging its bearer’s sins.

When Biagino turned back away from the window, for the briefest of moments, Carlo’s face appeared to be made of dead flesh and fearful to behold.

Biagino hid any sign of fear, but could not, for a moment, bring himself to speak. It appeared his oneiric visions were bent on plaguing his waking hours too.

In his dreams, for several nights now, Biagino had found himself back at the bridge of Pontremola, once more with the militia pikemen of Viadaza, his stomach knotted with fear as he witnessed the foe’s inexorable advance.

Just as in the waking battle, he became fascinated by the motion of their lifeless limbs, the glaring hatred somehow evident in the shadows of their empty eye sockets. They came on steadily, regardless of those that fell among them to bullet and arrow, like waves crashing on despite the rocks, neither slowed nor dismayed.

Everything was as he remembered – the way his hand slipped upon the hilt of his sword, the foul stench wafted on the breeze from the massed body of animated cadavers at the centre of the enemy’s line.

Then (every night) his attention was drawn away from the vampire duke’s advancing army, as it dawned on him that he was not where he thought he was, being instead on the southern side of the river, the waters now lying between him and the foe. When had they moved back across the bridge?

Why had they changed their plan of battle? Why could he not recall the retreat? Still, he thought, perhaps it is better to be on this side, for then the enemy must ford the river to reach us, being weakened in the attempt? This glimmer of hope, however, died almost instantly, as something else caught the corner of his eye. In that moment, his neck stiffened and the air suddenly congealed about him to become an invisible force pressing against him. With effort, he forced his head to twist so that he could look at the men by his side. In turn, they looked back at him.

Every face sported a fixed, fleshless grin, while their bony hands clutched at splintered and aged pike-shafts. Every pair of eyes was sunken within black, bottomless pits, and peered at him as if awaiting his commands. The nearest opened its mouth and shrilled an ear-splitting silence …

… causing Biagino to stumble, weak-kneed from the ranks, then tumble face-down onto the ground.

Then a shadow fell across him, which took away not just the light but the warmth too – the shadow of something bent yet strong, its head horned, his hands clawed, wielding a blade almost as big as itself.

Finally, just as he expected the huge shadow-blade to slash down in a brutal strike, the shadow’s other hand reached out, as if to haul him up, and he awoke. Bathed in sweat, shaking and weak of bladder, he scrabbled from the bed, tearing off the sodden blanket as if it were the thing that had wound him into the dream.

What could it mean? He knew the dream was surely sent by Morr, for he had become adept at recognising his god-given premonitions, yet he could not even say whether it concerned tomorrow, next month or next year. All he could do, as ever, was suffer the wait until the meaning revealed itself.

In the meantime, he had questions to ask the fisherman.

“I’m told you’ve been back to Viadaza. Is this true?” Biagino asked.

“For my sins, father, yes.”

“Why would you go there?”

“To get my best boat,” said Carlo. “I thought maybe the dead would not think to watch the sea.”

“And do they watch the sea?”

Carlo shuddered. “They do.”

“Oh,” said Biagino. “Well you are brave. Better than that, you’re lucky. I ask you now to be helpful too. Tell me what did you see? Exactly. When that’s done, I shall pray to help you put it from your mind forever.”

“Yes father, I’d like to forget,” said Carlo. He took air, as if about to jump into the sea, then spoke.

“I got into the bay after dark. This was not hard for me as I know it like the back of my hand – every shoal, every rock, how the currents play in the tides. It was darker than ever before. Not one fire burned in the city, not one window was lit by so much as a single candle. I suppose the undead do not need or want light. But the moons were waxing, which gave me light enough to get my bearings. Dark shadows divided the buildings, everything was black and grey. I couldn’t descry any boats at all, and thought maybe they’d been hauled up further than usual. So I paddled closer.”

Dong!

The bell’s ring grew louder.

“That’s when I spied them, father. I took them to be Lord Adolfo’s warehouse guards, brute ogres from the east. An’ I suppose they were … or had been before. Now they looked not just mean, but wrong. Their flesh had changed – it was torn, bloodied, blue! And pricked with bones. They had skulls dangling all about them. And they stank – not of sweat and dirt like before, but worse even than rotten pork too long at sea. I could smell them, despite being some distance away.”

“I knew two of them. I’d seen them many a time, guarding gates or addled with ale in the typpling house by the north-gate. Ugly brutes, they were, with dead-eyes that looked right through you. Now their eyes really did look dead. One of them carried a mast, I think, from which hung a string of bleached skulls. Another carried a gravestone as if it were merely a piece of flotsam.”

Dong!

Rang the bell. It must be entering the street now, thought Biagino. Carlo had not yet seemed to notice.

“There were half a dozen of them. Standing stock still, like statues.”

“Then I spied another, smaller than the rest, its back to me, and I knew the others were ruled by him. He had horns upon his head and shoulders, and he bore a brute’s blade. Enormous it was, which he hefted as if he were as strong as any of them and it was no burden to him whatsoever.”

Biagino’s throat tightened, for in his mind’s eye he could see that blade’s shadow.

“Even before he turned,” continued Carlo, “I could tell he knew I was there. And when he did turn, slow and deliberate, like he wanted to rub the fear in deep, his red eyes found me immediately.”

DONG!

“In truth, father, I think he’s been watching me ever since.”

“What …” said Biagino, his voice faltering. “I mean, who was it?”

“It was no man, but it was Lord Adolfo. Twisted most foul, baring teeth, talons and horns. Yet still Lord Adolfo.”

DONG!

Biagino could now hear the clattering of the bell-cart and the creaking of the wheels, and a familiar voice preaching Morr’s hatred of the walking dead. The light of the flagellants’ torches flickered into the room. Glad of the distraction, he turned to the window once more.

His heart racing, Biagino watched and spotted Father Antonello (as usual) leading the procession, sword in hand. Behind him came the first of the flagellants garbed in priestly reds and greys. One had somehow set a burning crown of iron upon his head, and yet still walked beside the others. (Surely some sort of clever illusion?) Biagino was surprised that Antonello would stoop to using stage trickery. The other flames, born on torches, were real enough, as was the battered and bruised state of the self-tortured flagellants carrying them. The bell cart was decorated with pages of scripture and an inevitable hourglass. Two robed men struggled with all their might to push it.

DONG!

Biagino turned back to the room, his heart a little less troubled.

“Thank you, master Carlo. Your report will be passed to those who need to know. You have done good service, and holy Morr will assuredly reward you. As promised, I will speak of you in my prayers. For now, however, make do with some broth and some ale. You’ll find both in the kitchen below, just tell the servants I sent you.”

When Carlo had taken his leave Biagino looked at the mad rabble of flagellants processing along the street in the wake of the bell cart. He did not really see them, however, for his thoughts were elsewhere.

Lord Adolfo was indeed now a vampire, just as the Urbimans had claimed.

And he still ruled Viadaza.

And he had been in Biagino’s dreams for some time now.

…

To see how the undead ogres were modelled and painted, take a look at Undead Ogres

—-

End of Spring, 2402

Part One: Not Gormless

South-eastern Tilea

As soon as he saw the burnt-out tower, Big Boss Gurmliss knew where he was. The ruin was no more than a mile from where the mob had been camped when he left them two weeks previously. They might not still be there, but once he found the camp’s site it would be very easy to follow their trail. Greenskins were not what you would call tidy, and even if they made an effort to hide their passage, Gurmliss knew all the signs to look for.

“Boss,” came Frabble’s urgent voice. “I knows this tower. We was ….”

“Ssh!” ordered Gurmliss.

Someone was approaching. He always seemed to know when someone was creeping up on him, though which of his senses did the work of revealing the fact he had never quite pinned down. He unsheathed his heavy bladed sword and rested it upon his chain-mailed shoulder.

There was a skittering sound, the clatter of stones, and then a familiar goblin lurched around the tower, his unsteadiness due to being hauled by pack of rats.

Known as the Ratter – on account of his constant companions, four mangy, red eyed rodents – his real name was Mig.

Yanking upon the leads to bring his rats to a jerking halt, he cocked his pistol by rubbing the hammer upwards against his shoulder.

“You came back then?” Mig said, scowling at Gurmliss and the other two survivors.

Gurmliss laughed, wondering if the sight of his unsheathed, bloodstained blade had prompted Mig’s unfriendly preparations, or whether such suspicion was due to yet another shift in power in the mob. Out of the corner of his eye he saw that his companions had both knocked arrows to their bows, and it suddenly dawned on him that all this nervousness could result in him playing a deadly game of piggy in the middle. So it was he cut short his laugh and answered quickly,

“Ain’t it somewhat obvious I’m back? Yer lookin’ right at me Mig. It’s not like ya need them rats to sniff me out. Ya thinkin’ I’m all ghostly?”

“I see you,” said Mig. “An’ I see only two gobs wiv you. So, I reckon you left some behind.”

“Some, yeah. And before you go a-askin’ where our snarlers are, we’ve got wolf flesh in our bellies to answer that question. Tasty too.”

Mig’s lips curled to reveal two fang-like teeth, and he pulled on his rat-pack’s leads.

“These are mine,” he warned. “An’ if you get to thinkin’ you’s wantin’ some seconds, I’ll set ‘em on yer! Then we’ll see who bites who.”

“Don’t you go worrying. We’s all full up,” said Gurmliss as he patted his chainmail clad belly. “Never mind yappin’ about dinner, I’ve come back with stuff to tell and I wanna know who it is I’ll be telling it to, and where they are.”

It was Mig’s turn to laugh.

“Oh, so Big Mosher and his boys didn’t want you then? That’s why you’re back, lookin’ for your old mob to take you in? I bet all your missing gobs and snarlers are in orc bellies not yours.”

“Look here,” said Gurmliss, “I said I was going to see what they were up to and that’s ‘xactly what I did. I’m back ‘cos I was always coming back. Besides, even if I was the naughty gob you think I am, there was barely anything left of Mosher’s mob. They can’t decide what to do and so they’re doing a bit of everything, some going this way, some going that. And what with an army after them, they’re doing it all quickly. Mosher’s got no more’n a dozen to boss around now. Even the Bull’s left him.”

“An army after them? What army?”

“Same as that smashed and bashed us at Tursi, o’course, with its stinking powder smoke an’ a gun in every hand. An’ it’s on its way here right now. Seems Old Firgle was wrong – leaving the orcs didn’t shake the men off our tail, and now they’re pickin’ us off one by one. So, tell you what, I’ll ask again and we’ll make this the last time shall we? Where’s the mob and who’s in charge?”

Mig had become fidgety, something his rats seemed to sense, their fur bristling, and when he spoke Gurmliss could tell his mind was elsewhere.

“Old Firgle ain’t running things no more, on account of him being dead,” he said. “Moonface Dulldrood’s the boss now. The mob ain’t that far away, neither. I can show you.”

“Moonface’s in charge! How low can the mob sink? Old Firgle was bad enough, with his gammy foot, but I’ve seen Moonface struggle to work out how to unsheath his blade never mind use it in a fight.”

“He ain’t one for scrapping, true, but he’s got ideas he has. He says he can read man words for one, and he knows how to mix up black-powder – good stuff an’ all. I got’s it in my pistol right now. Most important, he knows how to get secrets from the stubbornest of gobs.”

The last part got Gurmliss’ attention.

“What gobs? What secrets?” he asked.

“One of Scarback’s runts. Whispered to a blabbermouth that he knew where some great prize was, something the ratmen would pay a lot more than a lot for. Moonface got him to say it a bit louder.”

Even Frabble, not the brightest of goblins, was interested now.

“A ratman prize?” he said. “Gold and glitter? Magic and machines?”

“Dunno,” said Mig. “Don’t think the runt knows either. If he did know he’d still have some fingers and toes. But he knows where it is, an’ Moonface reckons when we get it we can buy our way out of Tilea.”

Gurmliss did not like the sound of any of this. Ratmen were most cruelly peculiar creatures, who were reputed to back-stab each other on a regular basis, never mind others they had dealings with. And the thing they treasured most was a burning kind of poison, or so he had been told. Worst of all, he wouldn’t trust Moonface to keep his wits about him when assailed by an angry bee, never mind when dealing with a ratman warlord.

“Be a good lad, Mig, and take us to the mob like you said you would. I think I needs to have a word or two with Moonface.”

—

End of Spring, 2402

Part Two: Dis Ducibus (Directed by the Gods)

The Northern Stretch of the Via Diocletta, near to Remas

Almost every day, around this time, Frediano crossed the road here, invariably burdened with a snapsack containing a loaf wrapped in linen, a pot of soft cheese or whatever else his mother had packed to take to his grandmother’s hovel. His grandmother had simple tastes and was always grateful, fussing over him and offering something seasonal she could gather nearby, either olives from her garden, an orange from the little tree by her door, or more often a cup of goat’s milk from Rubina. And she always shared the bread saying:

“That’s too big a loaf for me. You have some, sweet boy.”

Today Frediano was stuck on the wrong side of the road, his growling belly forgotten as he gazed at the unexpected traffic.

He could have crossed the road before they reached him, but on spotting the vanguard of the column he forgot his errand and stumbled to a halt, standing wide eyed and curious. A lone trumpeter led the way, mounted on a fine black horse, something like the sort that lords use for hunting but more slender and graceful.

Of course, he had seen soldiers on the Via Diocletta before – little companies of mercenaries with crossbows, pikes and colourful clothes, sometimes riding nags but most often afoot, their nags pulling wagons. But these soldiers were different in every way.

They were cammelli riders, with a double-pennant banner fluttering high above them, accompanied by the booming sound of the largest drums Frediano had ever seen.

Their clothes were mostly loose, white linen, with blue or red scarves, either around their waists or coiled about their heads, and some wore heavy chainmail. They carried shields of strange shapes, decorated with golden orbs and tassels of golden silk. They sported neatly curled beards, shaped rather more elegantly than the mercenaries wore. Their spears were almost as long as pikes. Strangest of all were their mounts – hulking beasts with overlarge heads, lazy eyes, spindly legs and large fleshy lumps heaped upon their backs to provide a cushion upon which to strap a saddle. Although he had heard of cammelli, he had never seen one before. They were not how he had imagined, being much uglier than horses.

“Not them orcs we was expecting, are they?” came a voice from behind, startling him. “The ones everyone was going on about.”

It was Peppe. Frediano had been so fascinated by the soldiers he not noticed Peppe’s approach, nor did he turn to look at him now.

“Arabyans,” Frediano said.

Peppe sniffed. “I know, Freddy. They’re called the ‘Sons of the Desert’.” He sounded all matter of fact, as if he were accustomed to witnessing to such sights. “My papa told me all about them. The boy king bought them to fight the greenskins.”

“But the orcs have been already beaten by the northerners down in Alcente!” said Frediano.

“They have. And now that the northerners beat them to it, this lot are going north.”

“Where to?” asked Frediano.

Peppe laughed. “Your mama and nonnina should not keep the world from you. You must know there’s a war in the north, vampiro and scheletri?”

“Everyone knows that.”

“Well, all the soldiers are supposed to go and help.” Peppe sniffed. “An’ it looks like they are.”

“Do you think the vampire’s soldiers will be scared of cammelli?” asked Frediano, noticing now how much larger than horses they were, lifting the riders at least another foot from the ground, if not more.

“I don’t think they’re scared of anything,” said Peppe.

Frediano noticed his friend was watching the riders just as keenly as him.

“No. I suppose you’re right,” he said. “The vampire’s soldiers do all the scaring themselves.”

“I’ll bet these Arabyans will have seen all sorts,” said Peppe. “Desert goblins, sand devils, maybe even walking skeletons from beneath the ancient cities.”

Frediano studied the face of the nearest arabyan, who stood beside a cammello heavily laden with packs and sacks, wondering if he looked like a man who had seen it all. The man looked back, right at him, then winked! Without really thinking, Frediano waved silently in return.

…

Morr Helps Those Who Help Themselves

Remas, Outside the Palazzo Montini, Residence of the Arch-Lector of Morr

Father Gonzalvo was alive.

Like everyone else, Biagino had believed Gonzalvo was cut down with the Viadazan swordsmen during the Battle of Pontremola. Gonzalvo had been at the fore in the thickest of the fighting, yet when he was wounded, he was not killed, and had lain unconscious among the corpses at the river’s edge. The blood and mud meant he was unrecognised the next day, when he was taken away with the worst of the casualties in wagons to Rapallo. Having barely regained his wits and being only just able to walk when the undead arose throughout the realm of Viadaza, he fled with a farmer’s family to Scorccio, remaining there until he recovered fully, both body and mind, from his ordeal. He was, however, not quite the same man as previously. He had become so utterly obsessed with fighting the undead armies of the north that he had no conversation, nary a thought in his head, that did not pertain directly to that cause. He had become the very quintessence of a holy warrior.

Which is why, perhaps, that it was Gonzalvo and not Biagino who stood beside no less than the Morrite Lector of Viadaza, Bernado Ugolini, and the arch-lector of Morr, Calictus II himself.

While these high clergymen watched the military parade in the street, Father Gonzalvo raised his hand to bless each passing company of soldiers.

The Reman captain-general, Duke Scaringella led the parade upon his colourfully barded horse …

… dipping his lance as he passed by the arch-lector’s palazzio and the gathered clergy. Behind him came several palace guards, including an ensign carrying the colours, two drummers and four sword-bearing sergeants. Other palace guards stood behind the arch-lector and other clergy, while a halberdier company stood in order to his left.

The arch-lector himself was immediately flanked by Lector Bernado and Captain Soldatovya, the mustachioed Kiselvite commander of the palace guards, while a priestly secretary stood a little behind in case his holiness needed him for anything.

Father Gonzalvo had saved his most impressive and powerful prayer for the great engine of war which was the focus of the procession.

Designed and built by the famous, polymathic genius, Angelo da Leoni, it was a mighty contraption of iron and timber intended to smash the undead legions, with both its own bodily weight and that of the lead and iron shot it could bring to bear.

Buried inside its sturdy, timber hull was a steam powered engine …

… its clanking, grinding, red-hot heart fed coal by two sweating crewmen.

Aloft was an iron-armoured platform mounting an impressive artillery piece of nine barrels and several more brass patereros besides, about which the liveried gunners busied themselves to fire occasional shot-less salutes for the encouragement of the crowds.

Da Leoni himself, like the master of a ship, was directing his invention, dressed as the other crewmen in Reman livery …

…honoured to be joined by the arch-lector’s own standard bearer, whose crossed keys flag fluttered from the rear as they trundled along the wide street.

The genius was deep in thought, listening to every croak and rumble from the engine below, occasionally breaking from his reverie to shout correctional instructions down through the peep holes drilled through the upper platform’s base to allow communication with those labouring down in the darkness and steam of the lower deck.

The engine was an important part of the arch-lector’s army. Everyone knew that the priests of Morr were dedicated to thwarting the undead, and served a god who hated the undead more than any other, either deity or mortal. In battle their magically potent prayers could gift soldiers with a portion of Morr’s hatred so that they fought all the more bravely.

Yet it was commonly held that, “Morr helps those who help themselves”, more warmly welcoming such people into his heavenly garden in the afterlife. The city had indeed done so, raising a great sum of money to pay for this modern, monstrous machine of metal and oak, the result of a brilliant mind, ingenious craftsmanship, and hard, skilled labour.

Just ahead of the engine strode another priest of Morr, repeatedly chanting the words of a blessing not dissimilar to Father Gonzalvo’s. Rarely, even in the city of the gods, had so many prayers and blessings been poured upon something other than a mortal soul.

It was as if the engine were being transformed into a carroccio, not by loading it with holy relics, but by washing it with prayers for hours on end.

In contrast to the constant, priestly intonations, the vigorous beating of the drums, and the steaming judders of the steam-powered workings, the watching crowd fell silent as the engine passed by. Although the citizens had cheered every company of soldiers as they came into sight, the monstrous, horseless engine was so strange to their eyes that their voices invariably petered out in awe.

This was not magic, nor illusion, but an ingenious, artificial construct so heavy it ground up the road, and so well armed that it must surely prevail against the enemy. It had been a topic of conversation at every inn, typpling house and tavern in the city, and so many hopes were pinned upon it, that it could do no other than draw everyone’s eyes.

Behind the engine marched an impressive mercenary pike regiment, their pike shafts painted near the tips with the colours of Remas, while many of the soldiers sported at least some clothing in the blue and red of Remas.

But neither the crowd …

… or the clergy …

… were much impressed by the pikes. Not having witnessed the might of the engine only a moment before, and still with the brimstone-tainted, smoky-steam lingering in their noses and upon their tongues.

Now, at last, thought many in the crowd, Remas is ready to go to war.

…

Note: Go to Tilean Steam Tank to see how the scratch built steam tank was made.

End of Spring, 2402

Part Three: Occupations

A Letter to Lord Lucca Vescucci of Verezzo

This to my most noble lord, from your loyal and obedient servant Antonio Mugello, being an account of my continuing travels in your service to gather true intelligence from the lands surrounding the beautiful realm of Verezzo.

Having tarried sufficiently long in Remas to dispatch my earlier report, I determined to make my way to the newly conquered realm of Trantio, there to discover how that realm fares under the dominion of the conquering Duke Guidobaldo Gondi of Pavona, as well as to do what I could to ascertain the Duke’s intentions. Upon the day of my departure from Remas I witnessed the arrival of a regiment of brute ogres, accompanied by brigand archers, all hailing from the northern realm of Ravola. They processed through the streets led by several chanting priests of Morr, and all those who witnessed their passage declared them to be the strangest of crusaders – a quite unexpected addition to Morr’s holy army, yet not at all unwelcome.

I know full well that the people of Verezzo grow daily more concerned at the Pavonan duke’s conquests, for if both Astiano and now the entire city state of Trantio have fallen to him, then it is not inconceivable that the duke might turn his inquisitive – nay acquisitive – eyes upon Verezzo, especially in light of the Gondi family’s continued yet entirely unworthy and unwarranted complaints concerning the annulment of Lady Leonara’s marriage. Like so many recently ennobled families the Gondi’s pride has the sharp, hot edge born by those who still worry about their worthiness for such rank. Thus it is that Duke Guidobaldo is said to be as angry as ever at the unfortunate misunderstanding over his niece, although it is also whispered that he stirs the coals only to ensure he has a complaint ready to hand as an excuse for future military action.

Upon arriving at Trantio, in the guise of a Reman petty-merchant, I immediately learned how oppressive is the new Pavonan rule, being not one jot less than that of the tyrant prince Girenzo, indeed, probably more so. The city was in a state of alert, having just learned that a sizeable army of mercenary ogres was upon the Via Nano with unknown intentions yet sensibly presumed to be unfriendly. This added to the native populace’s sense of unease over Duke Guidobaldo’s declaration that his surviving son, Lord Silvano, was now Gonfaloniere of Trantio, to become its de facto ruler when the duke himself left. Nor was the barely hidden bitterness ameliorated by the news that the region of Preto had been subdued, what resistance there was eliciting cruel reprisals by the Pavonan soldiery. This meant that the whole realm was now as one again, the city of Trantio – the town of Scorcio and the olive groves and vinyards of Preto – but it is a unity bought at a high price: the tyrannical oppression of Duke Guidobaldo. Ancient, proud Trantio has become a mere servant to Pavona.

I lingered a few weeks to better judge the people’s mood and to learn what I could of the strength of the Pavonan forces present there. Here I humbly direct your attention, my lord, to the document accompanying this letter in which I attempt an accounting of said forces. Before I left Trantio to continue my journey I learned that a large fortified camp was being constructed near unto Scorcio. This seemed somewhat to alter the mood in the city, the common people now believing it possible that Duke Guidobaldo’s promises of Pavonan protection against the incursion of the dead may indeed be true, and that rather than simply burden them with taxes and impressment, the duke is indeed preparing to defend their realm. Nor is he intending to do so at the walls of Trantio itself, by which time the rest of the realm would surely have been lain waste, sacrificed to weaken and disperse the foe, but rather to make his stand at the northernmost borders, thereby halting the foe before they encroach upon the rest of the realm. Yet my Lord, you must not think this to mean I am certain of these matters, for I was unable to ascertain what exactly the Pavonan army intends to do next. Apart from a company of light horse sent to scout the Via Nano to learn of the mercenary ogres, I know not whether the rest of the army intends to remain at Trantio, occupy the fortified camp at Scorcio or march away to some other purpose. Duke Guidobaldo keeps his own counsel concerning such matters.

Thence I travelled towards Pavona itself, intending to reach that city in a week’s time. I write this from Astiano, which has become settled in its subservience to Pavona, and indeed has raised both a fighting regiment for their new master’s army and a militia to guard the town in Duke Guidobaldo’s service. I will send a letter to you as soon as I arrive in Pavona, where I hope to gain a much better understanding of the Pavonan’s intentions towards your fair city of Verezzo.

Ever and always your servant.

—-

Lodging and Victuals

Camponeffro, South of Raverno

“There’s nothing here for us. Nothing of any worth, anyway,” complained Pasquale for the third time that hour, his voice loud enough so that those riding behind him yet upwind could hear.

Tino answered, not bothering to turn in his saddle to look.

“You knew that, Pas, before we set off. We’re not here to loot.”

“Never mind looting, there’s not even food or shelter. Fields all barren, cattle stolen, and what few folk we’ve found in a bad way and a worse mood. We may as well be in a desert.”

They had ridden for three days now, one of several companies of Portomaggioran horsemen scouring different parts of the region, each assigned certain roads, villages or valleys, while some patrolled the forest edge at the southern border. The VMC’s army had done a thorough job of sacking the whole area – it seemed northerners were no less adept at plundering than even the most veteran of Tilean mercenaries. Now all that remained were the ragged survivors and scattered bands of brigands bolstered in numbers by the desperate and the dispossessed.

Tino carried a brace of long-barreled pistols in holsters upon either side of his saddle, and wore sufficient plates of armour to protect his torso and his upper legs, his lower legs enclosed in thick leather boots. His hat was a scrumpled but liveried affair, unlike his friend Pasquale’s, which was much larger and made more enormous by the huge panache feathers attached to it. This was not vainglory, however, for Pasquale was the company’s hornblower, and in battle it helped if his fellows could locate him with their eyes also when they needed to rally, for a galloping rider might not always find the breath to sound a particularly loud note!

Tino gently slowed his mount’s pace until he was riding beside his irritable comrade.

“You’re looking at it wrong. You should be glad that the northerners came to Tilea, for if they hadn’t fought Kurnag’s Waagh then I reckon it would have been us who had to do it.”

“Tino,I’ll tell you what I am looking at – this place!” countered Pasquale. “I’m looking at what the northerners did! They may be heroes for fighting against the Waagh, but then they did this, turning honest farmers into beggars and robbers.”

“Aye, they did. But I say again, you’re still not seeing it right. Why not be glad the northerners attacked here instead of Portomaggiore?”

“Oh, I’m ecstatic about it. I suppose next you’ll be telling me that I ought to be happy I don’t have to carry all the loot they took, and that the wine they stole would’ve given me a headache in the morning, and that …”

“Hush now,” interrupted Tino, pointing ahead. “No shelter you said? Look up there. That looks like shelter to me.”

It was a dwelling of modest size, which on first sight appeared as ruinous as nearly every other they had seen, but upon closer inspection was undergoing repairs, if in a haphazard and makeshift sort of way. The original roof was gone, replaced by a tangle of broken timbers supporting a stiff, canvass sheet. Faces peered from behind the walls.

Tino turned away from the company’s line of passage, to ride towards the dwelling. Three others, including Pasquale, followed him. The rest of the riders apparently did not share Tino’s curiosity and carried on with their own course, no doubt tired of this miserable land and its miserable and meagre pickings. Besides, the ruin was too small for all of them, so they probably knew they would have to find somewhere else for the night.

As Tino drew up, he saw that the three inhabitants were everything he had come to expect from this land – an old, bent man leaning heavily on a stick, a battered and bruised peasant with his arm in a sling, and a woman carrying nothing more exciting than a bundle of sticks.

“You there,” shouted Tino, having unholstered his long horseman’s pistol, a habit formed from bitter experience with brigands over the last few days. “Is this place yours?”

“What’s left of it, aye,” said the injured man in a thick Ravernan accent. “All ours. Why? Are you intending to smash it up some more?”

Pasquale laughed. “There’s not much left to smash, my friend.”

“You needn’t fear us,” reassured Tino. “We’re here to make things better, not worse. Stupid question, I know, but who did this?”

“Foreigners, of the ultramontane kind,” said the old man in a croaky voice.

Tino asked the question he had been using a lot recently. “Why?”

Now the old man gave vent to a bitter laugh. “Because this is what soldiers do. I know, I was one once.”

“No, old man. I meant why here and not somewhere else? Why attack Camponeffro?”

“They said we were being punished,” said the man with an arm in a sling. “I told them we hadn’t done anything to them and this is what I got.” He held up his injured arm.

Tino frowned. This was new. “Punished for what?”

“I don’t know,” said the wounded man. “Having hens? Being close by?”

The old man coughed and everyone looked at him. “They said: ‘That this will teach you not to throw Marienburgers out of windows.’”

Pasquale swept his hand as if to indicate all around. “Seems a bit too much punishment for a spot of tomfoolery and rough and tumble,” he said.

“That was their excuse,” said the old man. “Not their real purpose. When I was a soldier we found fighting greenskins to be a very unprofitable affair. The sort of things they treasured weren’t exactly what we wanted to loot. I reckon the ultramontanes came here because they needed pay, and plucked at any excuse to make their robberies seem like something more respectable.”

“You can tell us about your adventures over supper, old man,” said Tino, smiling. “In the meantime, wench,” he said, fixing his eyes on the woman with the faggot …

… “How about using your burden to get a fire burning? Oh, and what have you got to eat?”

Next Installment: Part 9