There’s More to Come

Luccini, Summer 2403

“Not bad, this stuff,” declared the Cooper Artur Scharff. In one hand he clutched a tankard, in the other a flask he had tapped some of the wine into so that they could all have a taste. Only the carpenter Gerino had refused, for he was distracted by a bottle of port he had found.

“Not bad at all. If the other barrels are as good, we should be selling this, not drinking it. With the price this’d fetch, we could buy five times its weight of the kind of wine our boys’d be happy with.”

“You saying we’re cheap?” asked Geoberto. “’Cos I’ll have you know my palate is as sharp as any connoisseur’s when it comes to drink.”

“You long since burnt away any palate you ever had with strong liquors,” laughed Artur. “Did for your hair too!”

“That was practice, long and hard,” said Geoberto, “which makes me the perfect drinker.”

They were discussing their ill-gotten gains on Luccini’s southern outskirts, where a wide path led from the city down to the Almond Sands. The city had a fine harbour, with wharves a-plenty for ships of every size, but it was guarded by two stone artillery bastions, so the Sartosan pirates had disembarked from boats on the sands then marched up to assault from the landward side. Now that Luccini was taken, most of the vessels had moved to the harbour, but a couple of ships and their boats, those belonging to Captain Garique, had for reasons only the captain himself really knew, remained at the sands. Which was why Garique’s crew were trudging back and forth from the beach, hauling their considerable share of the loot on the way down.

Not all of them, though, just the younkers and the foremast men. The sea artists and ship’s officers were busy drinking and talking. Artur was sniffing the wine, then allowing it to roll around in his mouth before swallowing. The others were either humouring him or had failed to notice.

He stroked one of the barrels and nodded in appreciation of the cooper’s skill.

“Seems to me,” he declared, “that we’ve already taken enough loot to satisfy the captains. We could disperse the fleet right now and there’d be no one a-complainin’, no bitterness nor disappointment and only praise for the admiral. And we took it easy.”

“Tell that to Oskar Furst,” said Gerino, who had started listening. Some of the port he had been sampling a moment before dribbled down his black beard.

The admiral’s first mate, ironically named Furst, along with a number of Volker’s own crew, had died before the Sartosans even got off the beach, shot by a troop of Luccinan pistoleri left behind when the young king had marched off to war against the ogres.

“Someone was bound to be hurt,” said Artur. “You can’t expect to take a city like this without a little blood spilled. But think, if the king had been here with his army, however meagre it might be, there’d have been a lot more of us than Furst an’ a few of his lads queueing at the garden’s gate.”

Geoberto laughed. “The queue’s long enough, what with all the Luccinans.”

“Their fault for arguing,” said the master-gunner, Isacco. “If they’d have had the sense to yield immediately, then everything would have turned out just the same, ‘cept they’d all be here to watch us.”

A pistol shot cracked from behind them, and they turned to look over the fence. One of Admiral Volker’s crewmen was responsible, from Furst’s watch, and was now stood over the man he had killed.

“Another fool arguing, no doubt,” said Isacco. “People should know when they’re beat, strike amain and submit.”

Isacco always had a sombre tone, a consequence of his somewhat pessimistic philosophy. It was said he had been a proper scallywag in his youth but had changed when a gun he was tending shivered and killed everyone around him, somehow leaving him with not a scratch, other than a missing toe.

“Maybe so,” said Geoberto, “But wouldn’t you complain a little if you were being robbed? There’s no need for real nastiness on our part, just the show of it would suffice. We’re taking everything else they have. We could at least leave them with their lives.”

They watched as the shooter rolled the corpse over with his foot, perhaps to see if he was dead.

“Let the fellow grieve,” said Gerino. “Furst was well liked.”

Gerino took another swig from his bottle, and Artur drew some more wine from the tapped barrel.

“You said we should sell it, not drink it,” said Geoberto.

Artur looked up as the red fluid trickled into his flask. “Can’t sell this one, now it’s been tapped. There’s plenty more.”

“This is all our share, then?” asked Geoberto.

“It is. The captain made good choices when it came to laying claim to portions. We should get some carts to take this lot down to the beach.”

Gerino pointed down to where a little stream crossed the path. “They didn’t wait for a cart.”

Peering down, they could all see two fellows struggling with a barrel just on the other side of the water.

“That’s but a little one, and I doubt it’s the same vintage. Still, I’ll see to it that they’re the last to try that. If they drop the barrel it’ll ruin the wine even if it don’t break right open.”

“That one’ll be for the captain to drink,” said Geoberto. “They’ll not drop it. Not just now anyway, what with him so close. He took a barrel for his cabin last time.”

“As was proper,” said Artur. “It’s in the articles.”

They could all see Captain Garique standing near the two with the barrel, with Tito Álvares by his side, toting his beast of a gun.

Garique had been supervising the removal of goods, utilising his unsheathed cutlass to point out which loot was to be carried next; ordering the tardy men to hurry up and those being careless to slow down. He was one of the oldest captains in the fleet, before that first mate to the admiral back when the admiral was only just elected captain himself. For some years he had been a captain in his own right, never once voted out, and well respected by his crew as a stickler for fairness (which was why it was only a small barrel he had taken for his own cabin). Bitter experience – the witnessing of so much treachery, cheating and trickeries – had made him very suspicious of the other captains, even the admiral. Tito was often by his side, with his many-barrelled handgun, just in case a point needed making in no uncertain terms. It rarely did.

Garique’s share included much more than the wine. Several chests of precious metal and gems had been allotted to his crew, from which he and the rest would obtain their proper portion.

As per the articles, the captain would receive four shares in the prize, the sea artists and officers two, the sailors one and the boy -being only half a man – a half. Some of the chests were huge, so big that a single man could not hope to lift them.

Those who were not lugging the loot were guarding its transit. The larger chests had blunderbuss and handgun armed escorts, while watchful sentinels were dotted all along the route.

Luccini’s pistoliers had successfully scarpered after their brief assault, and so could conceivably return. As it was not known where exactly King Ferronso and his army were, no one could be sure he was not on his way home right now. Mostly, however, they were keeping an eye out for other Sartosans. Driven by greed and possessing of some flimsy excuse about gambling debts, compensation or some other grievance, it was entirely possible that another crew might choose to interrupt the loot’s journey to the sands.

“The fleet’ll not be splitting up now, Artur,” said Isacco. “This has been just a taster of what’s to come. They say the brute Boulderguts took everything from the cities and towns inland, which leaves the coast all to us. I say Luccini was easy, and the next place will be easy too. The noble lords have taken their armies north. There’s nothing to stop us.”

“There might be plenty to stop us,” said Gerino. “I’ve been to Remas, and Portomaggiore and Alcente. They’re great powers. They can march an army away and still leave an army at home, if they choose.”

“So where is next, then?” asked Geoberto.

Artur swallowed his biggest gulp yet. “You might be right about Alcente and Portomaggiore, Gerino,” he said, “but Remas has been wracked by rebellion and riots, and has sent armies north and west. If the Remans have anything more than Luccini had to defend their walls, I’ll eat my hat.”

“And wash it down with wine?” grinned Geoberto.

“It’s all about surprise,” said Isacco. “Remas is too obvious. Rich, old and declining, it’s where everyone will be expecting us to go. We could take somewhere smaller next. Maybe Volker knows we can take Alcente or Portomaggiore? Maybe we only took Luccini first because it was the closest?”

“Or maybe Luccini was a trial?” suggested Artur. “Maybe the admiral wanted us to flash our pans to make sure we’re ready for the real fight?”

…

The Message-Letter

(An Introduction!) Somewhere in Tilea.

Three of the Grey Seer’s servants were making their hurried way to him. For an otherwise abandoned stretch of tunnel, there was a lot of noise as they progressed, what with the crunching of the gravel beneath their feet, the clattering of the lantern the servant Bolk held aloft to illuminate their passage, and the strained wheezing sound of Gradger’s mask-assisted breathing. All this was amplified by the close stone walls around them, conjoining and reverberating, so that when they did speak they had to shout – or, more accurately, squeal.

“Your message-letter, Farrgrin, important is it? Yes, yes?” enquired Gradger.

“Never look, never read, just carry,” replied Farrgrin. “That is my task-burden. Not for my eyes, see?”

Farrgrin glanced back to indicate that they were being watched even now, for Bolk had more responsibility than merely lugging the lantern. Whether or not Gradger, his vision undoubtedly restricted by the small, thick glass lenses of his mask, noticed the gesture, Farrgrin did not know.

“Has to be important,” suggested Gradger. “It is for the lord-master. He will not look upon petty gossip and chatter-drivel.”

“You are asking what you should not be asking,” snapped Farrgrin. “Best be silent, or I might suspect-believe you to be a spy-traitor.”

“Not-ever I,” said Gradger. “Always obey, never shirking.”

“Well and good, best for all,” declared Farrgrin, nevertheless tightening his clutch upon the scroll.

They were in one of the lesser tunnels, leading from a little used exit. There were no breeding pits, slave pens, manufacturies, mine entrances or fungus caverns along this stretch, and nor had there ever been. Perhaps it had originally been intended as a sally port, or an emergency escape route? Farrgrin cared not, to him it was simply a satisfactorily secretive option.

Gradger’s mask let out a strained hiss as he took a deep intake of breath, and Farrgrin knew another comment would follow.

“I ask-enquire only because of Josgrach,” he said. “His was important news – the collapse, shoddy work-failings, fools in charge – which angered the lord-master. Rightly so, yes, yes, rightly so. Important news it was and the end of Josgrach. Bearer of bad tidings and killed-dead because of it.”

“It is not-ever for us to question the lord-master,” said Farrgrin.

“But yet what of us, I ask and plead, if this is grave and disturbing news?” The nervousness in Gradger’s voice was very evident. “Are we to be blame-punished for the mere carrying of it?”

“The lord-master knows-sees that which we cannot,” said Farrgrin. “Failings, you said? Perhaps Josgrach failed too, see? Late-delayed, or talk-chattering too much to too many, see?”

Farrgrin picked up the pace a little, and began to outstrip Gradger, running almost beyond the limit of the lantern’s light.

“Listen well, listen hard, understand,” he continued. “Learn from Josgrach’s fate, not fear, but sense. What is important-necessary is that we carry this message-letter prompt, quick, secret. So keep up! And shut up! See?”

They were approaching the end of the tunnel, where it met with a well-used passageway close to the Grey Seer’s cavern-chambers.

“Here, now, the guards,” hissed Farrgrin. “Remember my advice-words and live.”

Gradger allowed himself to drop back further, so that Bolk was between him and Farrgrin. A moment later they rounded the bend to the junction.

…

A Letter Sent to Several Many Tilean City States

Autumn IC 2403

(Campaign Note: This letter contains its Pavonan author’s account of events. Just how close his account tallies with actual events I shall leave for you to decide. The pictures should be considered clues as to what truly occurred.)

This to be sent to all legitimate and honourable rulers of Tilea, for their better understanding of the foul Treachery performed at Verezzo this Autumn of the Year 2403, and furthermore, so they may know how the Lord of Pavona, His Grace Duke Guidobaldo Gondi, offered his help and protection to all the citizens of that realm in their time of dire need and great sorrow.

Upon returning from Remas and having learned from his subjects of the discovery of the remains of a camp near unto Scozzese, the Duke rode post-haste from the security of his ancient and noble city of Pavona with his gentlemen-at-arms to investigate. It was quickly apparent that goblins had indeed utilised the camp in question, no doubt being the same force that held Scozzese to ransom whilst the noble duke was abroad leading the pursuit of the brute-tyrant Razger Boulderguts. Keen to exact retribution, and to cleanse Tilea of goblin-kind so that no more realms might suffer at their foul hands, and without a care for the meagre size of his own force, Duke Guidobaldo rode forthwith in pursuit.

The trail led unto the realm of Verezzo, and when the outriders reported encountering several many citizens fleeing from trouble, Duke Guidobaldo feared the goblins had already set upon this realm, perhaps this time employing the violence they had threatened against Scozzese. Upon questioning the Verezzan citizens, however, it soon became clear that another kind of destruction had been visited upon them.

The citizens reported that soldiers, flying the colours of Portomaggiore, had arrived in strength at the estates to the north of the city of Verezzo, announcing they were there to take supplies that had been promised by Lord Lucca Vescussi. The soldiers then claimed Lord Lucca was still with the grand alliance army near unto Trantio, engaged in the war against the vampires, but that his orders were clear – that the army of Portomaggiore was permitted, by his command, to take whatever it required for its sustenance during this time of war, in return for the protection it provided the realm.

The citizens complained that they themselves had been given no such instructions, instead having been ordered to provide the army of the VMC with supplies stockpiled for that very purpose, which they had already done only two weeks previously. Furthermore, they asserted, noble Lord Lucca had already returned to their realm a week before, and so on that matter the soldiers were at best mistaken, at worst, lying.

The soldiers ignored these claims, asserting it was the citizens who were lying, and redoubled their demands. Then, when met with stubborn refusal, they began violently plundering everything of worth and value they could lay their hands upon.

News quickly reached Lord Lucca, loving father to all in Verezzo, who quickly gathered what meagre forces remained in his realm after his considerable contribution to the army of the Grand Alliance, and rode out to give battle to the robbers.

As well as his riders, being light horsemen from a wild region of the Border Princes who had served him for many a year and were glad to dwell in a more civilised land, he commanded a company of crossbowmen, stout citizen militia all …

… and the one gun remaining in his small arsenal – an ancient piece kept serviceable despite its archaic nature. He also sent word to the halfling militia of Terrene that they should muster and move as rapidly as possible to join him.

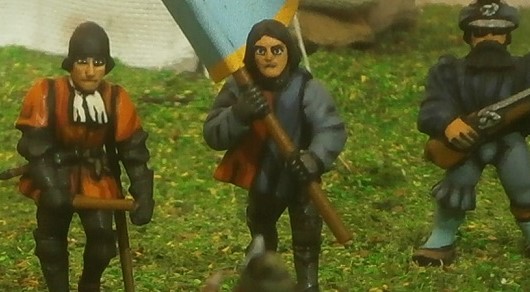

Upon arriving, Lord Lucca found a not inconsiderable force of what appeared to be Portomaggiorans arrayed before him, including a large body of brigand-bravi flying the personal banner of Lord Alessio Falconi – presumably a part of Falconi’s not inconsiderable household forces …

… as well as a body of mercenary crossbowmen, apparently Arabyan, perhaps being a lingering remnant of Gedik Mamidous’ Sons of the Desert?

Such bravi and mercenaries, by their very nature, might well be expected to indulge in plundering, but then Lord Lucca saw, to his horror, that among the robbers was a body of mounted men-at-arms, liveried in the blue and white of Portomaggiore, well-armed, armoured and mounted upon horses of quality.

That gentlemen might stoop to such wicked and ignoble action was offensive to Lord Lucca, as it also subsequently seemed to Duke Guidobaldo when he received the report. The two realms, Pavona and Portomaggiore, had been granted almost exactly similar liveries by accident of history, yet here was an action that demeaned the colours blue and white. Only ancient pride prevented our Duke from declaring there and then that he would change the livery of his own soldiers. He knew full well, however, that if any should change, it ought to be the Portomaggiorans, for it was they by their own actions (or so it seemed at that time) who had disgraced the colours.

Lord Lucca’s crossbowmen came on as best they could, to support the fast-moving lord and his body of light horse …

… but the Arabyans cut down many of them before they could even span their weapons. In return, the old cannon felled two of the enemy’s heavy horsemen, their armour as butter to a ball of iron, no matter how ancient the piece that hurled it!

Knowing he and his light horse could not hope to prevail in direct combat against such armoured riders as the enemy possessed, Lord Lucca led his men in a merry dance against the foe …

… adding their own short-bows’ arrows to the quarrels and round-shot of the rest of his force, buying time so that when the halflings arrived, led by the famous ‘Pettirosso’ himself, Roberto Cappuccio, the battle was still yet to be decided.

More of the enemy’s riders fell as the halfling’s proved their skill at archery, and while the regular archers of Terrene engaged in an exchange of arrows with the Arabyans …

… the bravi carrying Lord Alessio’s banner were badly stung by the Verezzan crossbowmen and turned to flee! The halflings, made bold by their successes, advanced, only to be severely mauled by the piercing power of the Arabyans’ quarrels. Faltering, they could only watch with horror as the enemy’s mounted men at arms charged and destroyed the Verezzan crossbowmen.

Then, just when the old cannon was needed, when the enemy had revealed the flank of their body to its muzzle, it failed to fire. The desperate crew managed to make it ready again and it did successfully fire, but its ball overshot the foe. The men at arms, perhaps angered by what the gun had done to them earlier in the fight, now charged the piece itself and mercilessly cut down the crew.

Lord Lucca, seeing his crossbowmen and artillery piece destroyed, and his brave halflings falling back upon the flank, suddenly saw an opportunity to inflict hurt and charged the bravi who had rallied and reformed close enough for him to reach.

Once again they fled, as soon as he launched his charge, and he soon realised his error, for in attempting to close upon the foe, he had opened his riders to a charge from the enemy’s remaining mounted men-at-arms.

His pursuit faltered as he attempted to regain order, then turned to flight when the enemy did indeed come thundering towards him. He and his light horse, who would normally have easily outstripped such a heavily armoured foe, where so disordered by casualties, and their failed charge against the bravi, that they could not escape. To a man, the noble Lord Lucca included, they were hacked down and trampled into the dirt.

And so it was that Lord Lucca was killed by thieves and murderers, while fighting to save his citizens from those same wicked men.

Made furious by all that he heard, Duke Guidobaldo immediately rode on, in the hope of closing with the supposed Portomaggiorans himself, but they had already fled the scene of their crime, further proving themselves to be base rogues. The duke found only one of them remaining, a fool who could barely stand for having drunk too much of the looted wine. When this man was questioned, the truth was revealed, and it proved no less horrible than that which had been believed before.

The murdering looters were not Portomaggiorans at all, but rather had deliberately disguised themselves as such. They were hired-soldiers of the VMC, most likely sent thither to stir up dissension between Tilean states, and at the same time to take more than that which had been agreed.

Northerners are well known for their cupidity, being in many ways no better than Sartosan pirates, only dressing up most of their robberies as legitimate trade, with papers, tickets and receipts to mask the true nature.

Here they had gone one, terrible step further, for they had clothed themselves as Portomaggiorans, even carrying Lord Alessio’s banner, so that they might shift the blame for their depredations, despite having declared themselves to be allies of both Portomaggiore and Verezzo, willing to march north to assist them against brutes and vampires. In truth, just as they came last year to Camponeffro in the realm of Raverno, their true goals were to raze and plunder, rape and murder.

And if not this worst of all possibilities, then at best the officers of the VMC had lost control of a significant portion of their mercenary forces. Perhaps their obsession with profit had led them to cut corners and hire scum little better than corsairs and outlawed bravi?

Whatever the truth, whatever the VMCs’ motivations, our noble Duke Guidobaldo knew he could not leave the citizens of Verezzo leaderless and without military protection. Not only would they be open to further abuse at the hands of the VMC’s soldiery, but also in this time of war against vampires, brutes and even scavenging goblins, they might suffer at the hands of a multitude of others. He also recognised that after the ravaging of his own realm by Bouldergut’s double army, the battering of his army in that struggle, as well as the fact that his son was fighting against the vampires with the grand alliance in command of most of Pavona’s soldiery, that he had insufficient forces to guard both Pavona and Verezzo effectively. Which is why he has offered all Verezzan citizens shelter in his own realm, welcome to settle in the ruined villages and towns left in the wake of Boulderguts’ rampage, thus re-populating those settlements.

Furthermore, Duke Guidobaldo even has in his possession a letter from Lord Vescucci in which the late Verezzan ruler proposed that the two of them ought to lay aside all past grievances so that they might more effectively support each other in the mutual defence of their realms in this time of emergency. Having received this touched the Duke’s heart, especially as Lord Lucca most likely lay dead before the Duke even read his words. His sadness was only magnified by the plight of the poor people of Verezzo.

So it is that right now the people of Verezzo, their goods and chattels, their livestock and servants, are being encouraged to travel to the safety of Pavona, so that they might both survive and prosper under Duke Guidobaldo’s protective care.

All praise be given to the great god Morr, whose embrace will comfort us through the long aeons after our lives, for working through his humble servant, Duke Guidobaldo Gondi, to ensure the people are also kept safe before they part this mortal coil.

…

Appendix

We played the battle, but I decided to recreate more artistic pics of certain moments and units rather than use the in-game pics. Instead I used the in-game pics as memory aids to help me set up the ‘arty’ pictures and to write the story of the fight. I laying casualties down etc before photographing = so that the pics told me what happened rather than the scribbled notes I usually faff about with. This technique helped me to play the game without too many distractions. (I played the NPC Verezzans.)

Also, we decided that as it was a small game (approx. 1000pts vs. approx. 750 pts) and because we had the time available (zipping through the turns with so few units and no magic) that we would play to the obvious end of the battle. As a consequence the game lasted 8 turns.

Here are a few actual in game pics, in order …

…

Scuttlebutt!

The town of Scozzese, in the realm of Pavona

The very end of Autumn, IC 2403

Pieter Schout, the army of the VMC’s chief linguister, had been making his way through the camp to attend upon the general, but as he had time to spare, he stopped to speak with Captain Vinco and one of the quartermaster-general’s clerks, who were inspecting a recently arrived wine cart.

“This is not good,” complained the clerk, Zanobi, his face contorted in disgust after having swilled half the contents of a little pewter can then spitting out the vile fluid. “Even thirsty soldiers on the hottest day would consider this barely drinkable. The merchants are mocking us, offering such as this for the price they expect us to pay.”

“Then it cannot be the same wine the quartermaster-general and myself tasted of,” said Captain Vinco, reaching out for the can. “That was a delightful tipple.”

The clerk pulled the can away. “I know you to be a brave man, good captain, but there’s no need to face this particular enemy!”

He poured out what remained, then folded his arms as he did so often, the empty can disappearing behind the loose sleeves of his orange doublet.

The captain bowed flamboyantly, as if acknowledging a gracious favour, eliciting a smile from Pieter.

“Dishonesty seems to be a trait shared by more than just the merchants of Scozzese,” said Pieter. “There was a similiarly deceitful air about the town councillors who spoke yesterday with the general. When we first arrived, they were welcoming, indeed ingratiating, but they turned suddenly sour when Duke Guidobaldo’s letter came …”

“That’s surely to be expected?” interrupted Vinco. “Considering the claims the letter contained concerning our own soldiers.”

The captain commanded a company of mounted handgunners, but himself preferred the full armour of a man-at-arms. He had just returned from a scouting foray and was even now plated from the neck down, although he had discarded his helmet to wear a feathered leather cap instead.

Pieter understood the captain’s point. Duke Guidobaldo’s letter had slandered the VMC, accusing them of attacking and plundering the Verezzan villages of Spomanti, even killing Lord Lucca in the process, while disguised as Lord Alessio’s Portomaggioran soldiers. As the Scozzese councillors were the Pavonan duke’s subjects, it was to be expected they would unquestionably accept their own lord’s account and vent anger towards the VMC.

And yet, even so, their anger had seemed tempered by some other, occult concern. In contrast to their curbed disquiet, Pieter recalled the flash of real anger in Luccia la Fanciulla’s face when she herself heard the letter’s contents. Hers was a far more substantial reaction than that of the councillors, despite her attempt to subdue her emotion.

She was a Tilean noblewoman, sworn before the goddess Myrmidia to serve in the army of the VMC, having accepted its cause was honourable. The syndicate of Marienburg trading interests forming the Vereenigde Marienburg Compagnie had been invited to defend Alcente from Khurnag’s Waagh and, having done just that, was now marching north to help defend the whole of Tilea against the vampire duchess. Luccia’s own honour was bound up with that of the VMC, which meant slandering it so abominably was a great insult against her.

Captain Vinco laughed. “I can imagine the discomfort they felt when obliged to question our general concerning their own lord’s accusations. There is no pleasant way to address such matters.”

“I witnessed their attempt,” said Pieter. “They had no reason to doubt the letter and approached the general nervously. What made them seem dishonest was the way in which they yielded so easily when General Valckenburgh said the accusations were utterly false, quickly asserting that they too were convinced of the same.”

Captain Vinco frowned. “So … you think they should have been more obstinate and called the general a liar to his face?”

“Why not, if they were honest?” asked Pieter.

“Cowardice springs to mind,” said the captain. “Or perhaps just plain common sense. It’s one thing for such men to defend their lord’s honour when among friends, quite another when faced by a foreign army like ours, especially when faced with the Lady Luccia.”

“You might have the truth of it,” Pieter agreed. “The general seemed to believe fear was behind their easy acceptance of his claim. If that was so, then they most likely still believed Duke Guidobaldo’s version of events, and were merely pretending to believe the general. Which is dishonesty. And if not that, then they were truly swayed by the general’s words, readily dismissing their own lord’s report as false, which is another species of dishonesty, for it breaks the bonds of loyalty between themselves and their master. Either kind of falseness would explain their sudden amenability.”

The clerk snorted. “Oh, they’re not that amenable, or they’d have delivered what was paid for, and not this vinegar!”

“Perhaps they feel guilty about accepting the general’s word over their own lord’s, and so thought to make amends by cheating us?” suggested Captain Vinco, grinning.

“If you have an understanding of Pavonans, good captain,” said the clerk, “then you have a rare skill my friend. I heard they banished every dwarf from their realm, simply because their stonework ill-suited the city and their skill in working metal made the city’s blacksmiths envious.”

“I’ll warrant the real reason was to do with gold,” said the captain. “Duke Guidobaldo will have profited from their forced departure.”

“Perhaps he just hates short people?” suggested Pieter, only half joking. “From the way those Verezzan halflings were talking yesterday, his hatred is reciprocated.”

Only the day before a company of halfling rangers had arrived at the camp, from the realm of Verezzo, where there was said to be an entire town and several villages populated by their kind. They too demanded an audience with the general, who had joked to his closest advisers that it was becoming hard to command the army what with all the guests he had to entertain.

“You mean that fellow they call the Pettirosso?” asked Captain Vinco. “Were you present when he spoke to the general?”

“Yes,” said Pieter. “It was thought a linguister might be needed if they spoke a halfling tongue.”

“I am aware of your considerable skills, but that’s a string to your bow I never knew you possessed,” said the captain.

“To be honest, it is more a dialect of the Empire tongue, and not too hard to learn. It turned out the Pettirosso spoke Tilean, as is the case with most Verezzan halflings. Still, I was ordered to stay nearby in case I were needed, and stood close enough to hear and see most of what was said.”

Captain Vinco looked surprised.

“Spying?” he asked.

“No, serving as ordered,” explained Pieter.

The captain and Zanobi stared silently at him, which confused him, until he realised they most likely had no idea what was said at the meeting.

“Well, I suppose it’s no secret,” he began. “I wasn’t ordered to keep it so. The Pettirosso brought news that the Pavonans had crossed the River Remo, as well as a quite different account concerning what exactly happened at Spomanti.”

“Everyone must know the duke lied in his letter,” declared Zanobi.

“Everyone here knows, of course,” said the captain. “I am certain we ourselves would have noticed if it was us doing the robbing! But the rest of Tilea may believe the duke’s lies!”

“Well, this Pettirosso fellow claimed the duke had done much worse than tell lies,” continued Pieter. “It seems the halfling and his rangers were there when Lord Lucca died, and their tale began very much like the Duke of Pavona’s letter. A force, Portomaggioran by their standards and livery, did indeed attack Spomanti.

Their beloved Lord Lucca rushed to its aid …

… sending orders to the rangers to support his counterattack, along with more of Terrene’s halfling soldiers. When they were defeated, their lord killed, the Pettirosso and his band were just about the only ones to escape. Knowing the land well and very talented at ‘sneaking about’, they not only evaded the enemy’s clutches, but were able to spy on the so-called Portomaggiorans.”

“‘Good at sneaking you say? How so?” asked the clerk.

Captain Vinco shushed the clerk, saying, “Hold your tongue, Master Zanobi. I want to hear what the halfling said.”

“No, no, I will answer,” said Pieter. “For to know the nature of he who delivered a story, is to better judge whether said story can be trusted. A ‘Pettirosso’ is what the Verezzans call a Robin Redbreast, and it is a somewhat famous nickname in these parts. His real name is Roberto Cappuccio. He was once an outlaw, a ‘goodfellow’ who declared a love of righting wrongs. They say he was the particular enemy of Lord Lucca’s tyrannical father, stealing from him and the cruelest of his officers, then doling out much of what he took to the poor. The story goes that when Lucca became ruler, the thief recognised the new philosopher prince was nothing like his father, and so daringly presented himself at court for wise judgement. To the astonishment of the entire realm, Lord Lucca praised him for his ‘good deeds’, then made him and his rangers, skilled archers all, part of the realm’s standing army.

Captain Vinco laughed. “Bravo! Quite the story. It would be fascinating to know the truth behind it. Still, I can see how knowing this Pettirosso’s reputation might colour our perception of what he had to say.”

“Maybe so,” agreed Pieter. “There could be layer upon layer of lies concealed in such a fellow’s words …

Nevertheless, he claimed the supposed Portomaggiorans, having stripped all the loot they could from Spomanti, moved off northwards. After a while they halted, burned the flags and changed some of their clothes – the knights, however, keeping their blue and white livery. Then a company of Southland’s crossbowmen, mercenaries for sure, and a handful of the knights went off further north, escorting the loot, while a regiment of bravi-swordsmen and the rest of the knights, along with their commander, headed off east-by-south. The Pettirosso did not want to weaken his meagre company by dividing them, and so chose to follow the loot, to learn where it was being taken.”

“You mean he wanted to rob it?” suggested, Captain Vinco, with a chuckle.

“I doubt he had enough in his band to attempt a robbery. He shadowed the little force, until it reached the river crossing over the Remo at Casoli. This, they claimed, proved their suspicions – the looters were not Portomaggioran as the duke of Pavona claimed, they were Pavonan’s, Duke Guidobaldo’s own men!

“Later that same day, the Pettirosso spotted our own scouts, and so, hoping to find potential allies, he came to us.”

Captain Vinco laughed loudly. “And, being a bold, little fellow, marched right on into our camp to demand an audience with the general!”

The clerk had a furrowed brow, obviously pondering all that he had heard.

“So, we have only the word of a famous ex-thief?” he said. “Whose dead lord happened to be the duke of Pavona’s particular enemy? What did the general say?”

“Oh, General Valkenburgh is ever the diplomat,” answered Pieter. “He thanked the fellow, expressed sorrow for his loss …

… but said that because he himself was no Tilean he would have to tread carefully when dealing with such serious accusations. Then, as a kindness, he offered the rangers employment as scouts for our army, howsoever temporarily, that they might not be without bread.”

“Ha ha!” laughed Captain Vinco. “A proud, strutting Robin Redbreast made to feel like a beggar!”

“Indeed,” agreed Pieter. “It may not have been the general’s best judged answer. The attempted act of charity altered the Pettirosso’s demeanour considerably – the little fellow’s face went bright red with anger, his eyes showing more than a glimpse of the rebel they say he once was.

As bold as you like, he launched into an impassioned tirade, telling the general that Lord Lucca was murdered by dishonourable thieves led by a cowardly and ignoble duke who disguised himself and his men. He said that such a crime went beyond robbery and murder, being an attempt to ferment war between several Tilean realms, and this at the very time all should instead be uniting to fight the terrible enemies from the north. Then he told the general that ‘treading carefully’ was not way to answer such a crime, and certainly not one that was even now ongoing.”

“How did the general take that?” asked Zanobi.

“As inscrutably as ever, as if no offence at all had been given, nor had any been intended.”

“He’s here to profit the company,” said Vinco, “not to get all distracted over local squabbles and Tilean honour.”

Now Zanobi snorted. “He was distracted a-plenty when he ordered the burning of Camponeffro as punishment for what the Ravernans did.”

“Aye, but even then the company profited … or at least made no loss, for we took everything of value before setting the fires,” said the captain. Then he asked, “Pieter, what did the general say to this petty arabiatti?”

“He just asked what the halfling meant by it being an ‘ongoing’ crime. It turned out that the stolen loot, on a lumbering, overloaded caravan, and guarded by a mere handful of soldiers, is apparently, right now, within our reach, still on this side of the river. The Pettirosso said that a quick force of horsemen, as well as his own lads, who to obtain revenge he promised would happily run until their lungs burned, could reach the loot and easily dispatch the guards. ‘You have horse soldiers, do you not, my lord?’ says he, as if making an idle enquiry at supper. ‘Why not act now?’ he asked, ‘And so retrieve that which was stolen. Let’s teach these murderers a lesson they shall not forget!’”

“Bolder and bolder,” said the captain.

“Oh, he did not stop there. When the general did not answer immediately, the halfling suggested that the Portomaggiorans, whose brave ruler Lord Alessio was even now leading the mighty alliance army in the north, would surely be more than grateful if the general both cleared his name and punished those who were attempting to besmear his reputation. See, the halfling knew nothing of Duke Guidobaldo’s lying letter proclaiming it was our men disguised as Portomaggiorans who had committed the heinous crime. The Portomaggiorans would be in the general’s debt, he says, as would all those who love the truth. Then, his impatience perhaps getting the better of him, he declared that if the general would not help him before it was too late, then he would find another way, or die trying. ‘I love my master for conscience sake, with all my heart,’ says he, and he would not risk allowing such a crime to go unpunished.

“When the general answered that he would have to consider the matter, and take advice from his Tilean lawyers, the Pettirosso finally went too far. He looked the general in the eye, bold as brass, and declared: ‘As you are merchants from the north, unable to understand honour, I will pay you half what was stolen, if you lend help, and if I am allowed to return home with the rest.’”

Captain Vinco shook his head in disbelief, with closed eyes, while the clerk rolled his eyes to the heavens.

“What did the Lady Luccia make of those words?” asked the captain.

“She’s not a northerner, so the insult was not directed at her. In truth, I know not, for she didn’t speak and I couldn’t see her face. But I doubt she was happy.”

“I think then, at last,” continued Pieter, “even the halfling noticed the mood had changed. Yet still, the general merely nodded, unperturbed, and said again that he would think upon it all. Then, before the ranger could dig himself any deeper, the general dismissed him, suggesting he and his men should eat, rest, and so prepare themselves for what must be done in the morrow.”

Next Installment: Part 25

One thought on “Tilea Campaign Part 24”