To His Holiness Bernado Ugolini, Most Highly Favoured of Morr, from your faithful servant, Brother Migliore.

The End of Autumn, 2403

I hereby and humbly present the conclusions of my research into specific aspects of history of the Uomini Ratto, as commissioned by yourself in light of the increasingly numerous reports of sightings upon the seas around, and even within the lands of, Tilea.

Concerning their ships

The uomini ratto are not natural seafarers, but can it be claimed that any land-born race truly is?

Perhaps the elves have perfected the art of maritime navigation more fully than all others, but even elven sailors must find their sea legs before growing accustomed to ship-board life. All vessels are subject to the vicissitudes of the seas …

… battered by winds and waves, pulled by currents, baked by the sun and befuddled by the light of the chaos moon. Sailors of all races fear being embayed on a lee-shore, or attack by corsairs …

… and there are none who are immune to ship’s fever, the bloody flux, scurvy or simple starvation upon a long voyage. Nevertheless, the uomini ratto must not be thought deficient in their mastery of the seas, for I have learned from the mariners of the holy city and Portomaggiore that the ratmen’s vessels have long been able to sail close-hauled on a bowline, indeed directly into the wind, being for the most part propelled not by sails but by screws affixed beneath their sterns, extending through their vessels’ bowels, powered by blasts of sulphurous steam made forceful by the conjoinment of the mundane and etheric heat of their sky-stones.

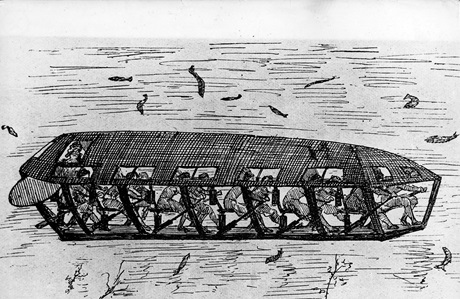

This means they can bear down upon a prize from leeward as easily as windward. Furthermore, even their tenders and their lesser, lighter vessels, of insufficient worth to warrant such infernal engines, are most often galleys, and as the uomini ratto care not a jot if their slaves are worked en-masse unto their very deaths, then they too can similarly speed through the seas, contrary to any wind, for several hours at a time, making it difficult for even the most weatherly of sailing ships to intercept them if they do not have the weather gauge.

Reports of uomini ratto in the gulf are on the increase. Yet a good number of sailors admit there have always been such sightings, indeed suggesting that nothing has changed, and that distance, the mist or the weak light of the crepuscular hours, encourages tired, hungry or fearful eyes to conjure a myriad illusions, some verminous. Although many a lost vessel has been blamed on ratmen pirates, it is rarely known for certain why any lone ship is lost at sea, for survivors from such vessels are few in number. Of those lost ships whose fates are known, the vast majority were travelling in a flotiglia – their loss thus witnessed, and few (if any) of those witnesses have ever mentioned attacks by uomini ratto. Yet, there are those who say that this in itself is evidential, for the ratmen are renowned as cowardly bullies, and as such prefer to prey upon weak and lonely prizes, which means no-one else would ever know their fate.

One particular curiosity concerning the uomini ratto’s sea-faring, is their reputed use of sub-marine vessels. No such vessel has ever been captured intact, but for centuries they have been reported and even known to ram ships. Whether or not these vessels are mostly propelled by turning screws or by oars none can say for certain, although in IC 2286, the Viadazan maestro Romolo Auriemma, apparently inspired by pieces of wreckage from just such a vessel, drew up plans for a sub-marine craft in which the protruding oars were made watertight using leather-sealed ports.

He seems to have constructed said vessel, but nothing is known concerning whether his efforts proved successful. This lack of information might be due to the maestro concealing evidence of its failure, or, alternatively, it is possible that the experiment was such a success that the schemata were thought to be too great an arcanum of state to be commonly perused. His rather dense treatise discusses many practical issues, concerning how to let out or receive of anything without the admission of water; how to propel and direct without the usual advantages of wind & tides, or the sight of the heavens; how to supply air for respiration; how to keep fires lit for light & cooking; as well as some rather obscure scribblings apparently detailing the leather seals and what appears to be fin-ended oars able to contract and dilate as required for either pressing upon or passing through the water. The last of his pages shows a weight suspended beneath such a vessel, to enable its descent and rising.

How similar the vessel Maestro Romolo made was to the kind employed by the uoumini ratto is, however, a matter of pure speculation, and so I shall desist from further consideration.

Concerning the Underpasses

In the library of the Palazio Endrezzi, I discovered the texts your scholarly adviser Stoldo Schiavone remembered perusing during his youthful studies. One of the volumes was missing, but fortunately the volume with a chapter considering the uomini ratto’s underground movements during the great war nearly two centuries ago was present and I scoured it for anything of possible importance. This I have transcribed here almost exactly as the original.

Excerpts from Anichino Didonato’s treatise about the Uomini Ratto Wars of IC 2212-15, Volume 2, Chapter 6: Concerning Caverns, Tunnels and the Great Underpasses

By the Summer of the year IC 2213 it had become generally known that the ratmen were emerging not merely from the ancient city sewers, as did their emissaries, assassins and spies so frequently during the past two, murderous decades, nor were they lodged en-masse in cavernous holds before their assaults, nor did they march by night to gather in ruinous places and wastelands and swamps, but that they issued in strength and line of march directly from the mouths of great underpasses, being tunnels of enormous proportions stretching for many leagues beneath almost the entire length and breadth of Tilea.

In early Autumn 2213 the army of the ‘Third Reman Pact’ fought at the mouth of the tunnel to the east of Remas, then also at an exit near Ebino, but in both cases, despite breaking the enemy’s forces on the surface, they were prevented from penetrating the tunnels to any real depth due to the loss of too many lives.

Such a sacrifice was considered a price not worth paying, for should the uomini ratto send another army through the tunnels, then the high cost of fighting underground could leave the armies left to face them critically weak. The mouth of the tunnel near Remas was collapsed with the use of black powder, but this proved of limited consequence, for the enemy simply carved out another portal further back, upon the eastern side of the River Remo. This allowed the Reman Pact to give battle at Stiani, where its forces were massed, in the summer of 2214, defeating and scattering a truly huge verminous horde, destroying their engines and burning mountainous piles of their corpses.

The underpasses were not as one might imagine, akin to brick-built sewers, nor even ancient, twisting, irregular caverns, between which a traveller might squeeze through skewed crevices and cracks. Instead, they were tall and wide enough for an army to march in column of ranks and files.

The following excerpt is taken from Chapter 2, ‘Concerning the Enemy’s Armies’

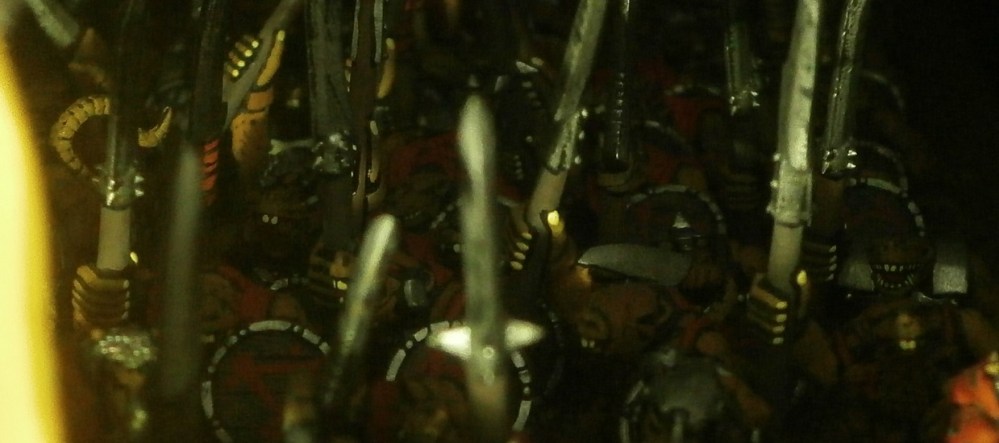

The uomini ratto fielded horde-legions with double or even triple the numbers of the Tilean armies they faced. These were divided into regularly sized, regimented bodies scuttle-marching in strict ranks and files. Each such body was commanded by a chieftain, accompanied by a bodyguard-lieutenant, several musicians with shrill bells and the bearer of a ragged banner.

Most commonly the warriors carried long bladed spears and round, iron-rimmed shields, being clothed in dirty rags with scrap-plates of iron armour on their upper bodies and arms.

Their natural proclivity to swarm, as might their tiny brethren when threatened by some cataclysmic event such as a flood or wildfire, meant that they had an uncanny agility even when packed together in the closest order. They marched this way also, as closely dressed as a body of Tilean soldiers might be only in the moments before engaging a foe.

Here Chapter 6 continues:

The great underpasses, and the mouths they served, were tall enough to allow the passage of engines of war of considerable size. Some engines were propelled by strange mechanisms, in which sulphurous steam was heated by shards of burning sky-stone to turn gears and consequently the wheels, as might river waters turn a mill wheel. Such was the unreliability of these engines, and the ever-present danger that they might self-combust or even explode, that they were most commonly moved upon the march by slaves. Both uomini ratto, and their larger brute cousins, were employed as beasts of burden, often together, so that while the smaller slaves were whipped to perform the bulk of the labour, the brutes were required to lend a more mighty hand as occasion demanded, such as when stuck in a rut, struggling through mud or upon an upward slope.

When transported through the tunnels, it seems that the engines were invariably removed from the main body of the army, most likely due to the relative slowness of their lumbering progress and perhaps also a reluctance to manoeuvre such unstable burdens in close proximity to the army’s massed soldiers. Any sudden detonation would surely have sent a wave of fire washing along the tunnels, capable of immolating many hundreds among the huddled hordes if it were to reach them before its heat was sufficiently dissipated.

Each engine, its slaves and matrosses, was governed by an engineer whose understanding was sufficient to coax his ward into destructive power as and when required. They often carried a shard of the precious sky-stone themselves, mounted upon a haft of iron, the function of which was unknown, but has been variously speculated to be either like unto a key, or be able to produce a spark with which to breathe life into the engine, or a stinging staff with which to berate and bully their underlings, or perhaps merely a badge of office to signal their own importance and professed mastery of the mystery of said stone?

How the underpasses were constructed is unknown for certain. What parts near unto the mouths were inspected closely by miners showed some scattered signs of chiselling, more frequently a swirling form of scraping, while other stretches seemed to have been scorched, the rock surface part-melted or glazed. Knowing the uomini ratto’s predilection to employ mighty machines in battle …

… as well as vast throngs of slaves of their own kind, then it was supposed that either one, or indeed both of these methods, were employed to hew through the rock. It is presumed the passages linked to natural underground fissures, for where else could the vast quantity of debris created by their mining, howsoever it was done, be put? Some scholars suggested that it were possible that the rocks were carried away by slaves, and indeed there are ancient tales, many hundreds of years old, of entirely new hills appearing in the far northern region of Albu (although the stories claim, among other things, that they were made as cairns for the eternal repose of giants or even that monstrous moles dwelling a thousand fathoms beneath the ground had thrown them up over-night when they came aloft to breath sufficient air to sustain them for another millennia).

The ground of the underpasses was like unto a beach, part-pebbled, part-sand, which in itself gave several miners cause to wonder at how exactly it had come to be so. It was suggested that perhaps the ground was a by-product of the pulverising of the rock, or some sort of burning?

The tunnel mouths at ground level, were the extremities of the tunnels extending from the underpass.

The underpass itself was thought to pass by Ebino, under the River Tarano just before the River Bellagio branched off, then beneath the River Trantino north-west of Scorcio, coursing on to the mouth of the River Remo, after which it corkscrewed up to exit through a sea facing wall of rock. Other, more elevated exits, required ramps to be made from the debris which poured from the mouth.

How the whole was ventilated was never properly discovered, and it could only be speculated that there were some form of ventilation shafts, perhaps guarded by iron grills or the like, with apertures cunningly concealed from the upper world.

Chapter 6, Part 2: Concerning the Collapsing of the Underpasses

Having had such limited success in collapsing the tunnel mouths, the renowned maestro Abramo Ruggiere of Urbimo was tasked with discovering a way to make the underpasses themselves impassable. He was chosen because of his successful engagements in great architectural works such as redirecting the Via Aurelia to avoid the flood plains west of Astiano and damning the River Riatti near Terenne to create an artificial lake, and his proven expertise in the construction of great, helical, grooved shafts screws with which to lift and direct water.

He proposed re-directing an artificial offshoot of the River Remo to permanently flood a long section of the underpass, while also using fiery conjurations and gunpowder to collapse the tunnel in the western reaches of Usola, south-east of Ebino. Thus, if either method proved unsuccessful, then the other might make up for the deficiency. And should the uomini ratto discover one operation before it was completed and devise some method to thwart it, then the same method could not be applied to the other stretch.

Other city states, including Miragliano, Trantio and Astiano, were expected to assume the responsibility of collapsing or otherwise preventing the use any tunnels in their own proximity, and it is possible that different methods were employed at these locations.

Both of maestro Abramo’s proposed methods proved effective. A torrent of water, drawn from the Remo, was poured through a large, carved hole into the underpass and flowed freely for several days until it began to spill out from the hole, presumably because it had filled the entire tunnel length, or perhaps the enemy had collapsed the tunnel at a removed point in order to block the water’s further onrush. At that point, as had been planned, the maestro ordered the damning of the Remo’s outflow so that the river might resume its usual course. Subsequently, a smaller channel was dug to ensure that the waters within the underpass would be replenished continually, thus replacing any lost due to flooding through underground fissures, whether natural or unnatural.

To the north, near Ebino, several fire wizards were employed to conjure a magically induced wave of flame to wash along the underpass, where large quantities of blackpowder, both barrels and grenadoes (the latter jammed into fissures in the rock walls) had already been placed at both frequent and regular intervals. It was presumed that each blast would add to the wave of flame as it flowed, so that as the ethereally derived power of the heat dwindled, the fury of the mundane flames would increase in inverse proportion.

Thus it was that the course of the war was changed considerably, for subsequently the enemy had to rely upon overland marches and the seas, and was much less able to conceal the disposition of their forces.

I have copied here, as best my limited ability allows, the little map included in the chapter:

Here the chapter ended. The remainder of the book concentrated upon the history of the Third Reman Pact and of the war itself, mainly concerning the politics and rulers of the various Tilean states involved in the war, as well as a veritable cornucopia of stories concerning the nobility, some important and others insignificant, but of very little consequence to our world two centuries later.

…

As you yourself wisely suggested, I discussed my findings, as well as all that I had learned from both the sailors and Anichino Didonato’s other volumes, with the maestro Angelo da Leoni. He allowed me to visit him in his workshop, where he was surrounded by books, papers, schemas and strange artefacts, the like of some of which I had never seen before. A large, spherical, globe of strangely-hued metal gave off occasional stuttering clicks throughout our meeting, but neither the maestro nor his gnomish assistant paid it any attention.

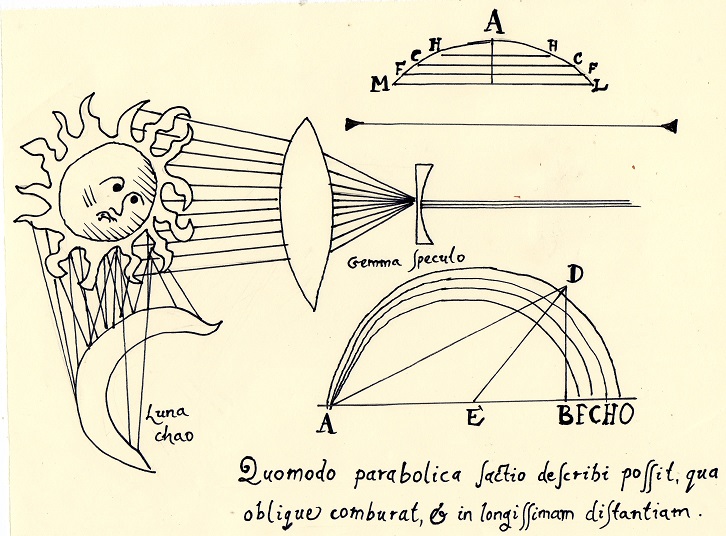

He clearly found my account fascinating and was prompted to wax both lyrically and generously in sharing his own thoughts. He seemed most intrigued by the possibility that the ratmen’s tunnelling engines, if they did indeed employ heat to burn the subterraneous rock – as the evidence of scorching suggests – might be, in form, rather like the engine he gifted to the Disciplinati di Morr for their march into the north.

That consisted, he told me, of lenses both dioptrical and catoptrical, some of pure glass and others of glass admixed with powdered sky-stone, being employed to separate, then concentrate a conjoining of light both etheric and mundane, vastly increasing the heat thereby manifested. Such an apparatus, especially if the source of ethereal light were not the distant sun but a shard of pure sky-stone, of a size and form that would most likely bake the very flesh of anyone standing close enough to work the device, might indeed produce a shaft of such brilliant intensity as to burn away the rock or at the least make it (to a depth of several feet) so brittle in consistency that simply scraping at it would subsequently cause it to crumble it away.

Yet he foresaw innumerable difficulties and dangers inherent in the employment of such an apparatus, not least the great cloud of poisonous fumes that he believed would be produced. Here he showed me several strange masks, hoods and sleeved cloaks he had fashioned, kept in a wardrobe in his workshop, intended to be worn at times of plague or when foul fumes tainted the air, and spoke of the possibility that similar garments might be employed to permit workers to labour at least for some time before succumbing to the noxious vapours.

Yet, still he checked himself, for he now declared such a sudden boiling, even of only the constituent part of rock that gifted the quality of hardness, and its almost instantaneous transformation into vapour, would certainly cause a great and violent on-rush of air, at most explosive and at the least like unto the strongest of gales. This would be forced unstoppably through the great tunnel to be released and diminished only wherever vents pierced the roof to reach the upper world, which surely there must have been. Indeed, he proposed that such vents, placed at regular intervals, would have had different purposes over time, from allowing air to circulate sufficiently to make work in the tunnels just possible, then later allowing the necessary escape of the bursting, noxious vapours. Perhaps some of these vents, he suggested, if only those most suitably placed, were then later transformed into the concealed ventilation shafts intended to serve the tunnel permanently?

Before I left, and as a most gracious gesture to show his respect for you your grace, he instructed his gnomish clerk to take a copy of a paper of consequence, that might better inform natural philosophers and engineers of at least the basic principles of his burning apparatus, if not the full and complicated practicalities of its construction, which were more discovered and explored in the making and calibration of the apparatus than in any schema or drawn design beforehand. I enclose said page here.

I remain, as always and forever more, your most humble servant, for you are holy Morr’s most blessed and my heart knows only love for him and all those who serve his church.

An excerpt from Bonacorso Fidelibus’s work: “The Many Wars of the Early 25th Century”

Autumn, 2403

Despite the hopes raised by the crushing victories against the undead achieved in the realm of Trantio, first at the necropolis valley of Norochia and then further north in the Trantine hills, as well as the news of the ogre tyrant Razger Bouldergut’s departure through the mountainous pass of the Via Nano into the Border Princes, the whole peninsula of Tilea remained wracked by war or the imminent threat of war. Great armies were on the move, alliance-forces combined and divided in response to this particular threat and that, and old enmities and hatreds continued, as ever, to interfere with the greater need.

The army of the VMC had marched all the way from Alcente upon the southern-most tip of the peninsula to Pavona. Its general, Jan Valckenburgh, was intending to join with Duke Alessio Falconi’s mighty army to drive the vampires once and for all to their destruction, but had instead become distracted by the reports concerning the ruler of Pavona, Duke Guidobaldo Gondi.

The Pavonan duke had claimed in a public letter that a force of VMC soldiers, disguised as Lord Alessio’s Portomaggiorans, had attacked the realm of Verezzo, killing the philosopher Lord Lucca Vescussi and plundering the region known as Spomanti. General Valckenburgh, having himself interrogated a band of Verezzan rogues fleeing the troubles in their realm, declared Duke Guidobaldo’s words to be lies, and that instead it was Duke Guidobaldo’s own Pavonan soldiers who had performed the foul deed, spurred by a greed for plunder now that their own realm was so weakened by the depredations of Bouldergut’s brute ogres, and hoping also to distract and damage all the realms around them, so that Pavona might not appear so weak in comparison.

Many argued over the truth of the matter. Some said that the Pavonan duke was guilty and had made the false claim simply to hide the fact that he himself was responsible for the raid and murder, cleverly befuddling the picture so that should it be commonly suspected that the Portomaggiorans were not to blame, he could respond with the second lie on top of the original deception. Others said that the VMC was actually responsible, being dishonourable plunderers by their very nature, and had used the lie as an excuse to go on from plundering Verezzo to taking more from Pavona also, all the while claiming to be entirely innocent, and so simply responding to Duke Guidobaldo’s outrageous defamation, as well as seeking proof of his foul deed to restore their honourable reputation!

Whatever the truth, the army of the VMC now drew close enough to lay siege to the ancient, mightily walled city of Pavona, wherein was garrisoned the last of the Pavonan armies. The young Lord Silvano, who had fought so bravely in the war against the vampires (at Viadaza, Ebino and Trantio) had only recently arrived home, given leave to depart from the grand alliance army after the victory in Norochia, where his men had not even needed to unsheathe their swords.

Lord Silvano’s father Duke Guidobaldo also returned, having travelled from Verezzo where he had offered sanctuary to all the citizens, promising them homes, livelihoods and protection in his own realm. Learning of the VMC army’s approach to his city, however, he could not tarry to escort those who accepted his offer, but raced ahead, arriving in the nick of time, only matter of hours before the army of the VMC drew themselves up to within handgun shot of the city walls, in preparation to lay siege. He was greeted by his son, but any happiness either of them might have felt at being reunited was surely dwarfed by concerns regarding the forthcoming struggle.

The VMC had marched north ostensibly to share the burden of the terrible war against the vampires and brutes, yet now they had instead embarked upon a war of honour against one of the oldest Tilean city-states, despite the vampire Duchess Maria’s complete destruction of the army of the Dedicati di Morr at Ebino, and the landing of an army of Sartosan pirates upon the coast at Luccini. It was muttered that their distraction proved their true nature as petty minded merchants, more keen to profit from war than face the true threats facing Tilea.

It is to Luccini that I shall next turn. King Ferronso had taken leave of the grand alliance army at Trantio as soon as he received reports of the Sartosan threat to the coastal realms.

He did not do so lightly, and indeed left a significant portion of his army’s strength with the alliance force, under the command of the condottiere General Marsilio da Fermo. The army’s council of war agreed that they had more than adequate strength to defeat the enemy force in Trantio, and so it would be unfair to demand that the young king remained with them when his realm faced such troubles.

But the journey home was long, and despite riding as fast as he possibly could, accompanied by his guard of noble men-at-arms, the king arrived too late to save his realm. The Sartosans had already landed in great strength, utterly overwhelmed the city of Luccini, plundering it thoroughly, then moved on to take all they could from Aversa to the east. Thus it was that the young king could only watch, more spy than warrior hero, as his realm was ravaged by an enemy far too strong to take on.

(To be continued below.)

…

All is Lost! Is All Lost?

They had left their mounts hidden deep in the woods, with the rest of the company, then the three of them, cautiously, if a little clumsily due to their armour, picked their way to the trees’ edge. Although he had already been informed of what was happening in Aversa, the young King Ferronso insisted on seeing with his own eyes, and his companions, for several reasons – not least that he was their king – chose not to argue.

Before they reached the boundary, they could hear the enemy, some laughing, others shouting. Signore Pierozzo went a little way ahead of the king and Barone Vettorio, stopping to beckon them on only when he had made sure it was safe to do so. It was a spot from which the town could be seen, but where the trees and bushes where thick enough to provide concealment.

There they watched a while in silence, until, as was proper, the king began to speak.

“All is lost,” he said, dejectedly. “If only we’d got here quicker. If only I’d left the Portomaggiorans sooner.”

“Your highness, you bear no blame,” said the barone. “We came as soon as we heard, and none but the gods could ride faster, not in armour at least.”

“Then we should have left our armour and used faster mounts. And we should never have stopped for sleep.

“And we would have arrived ill-equipped in every way to thwart such a numerous foe.”

“We are ill equipped, Vettorio! Why did I leave so many soldiers in Lord Alessio’s service? Why did I not bring them back with me?”

“Sire, you were honour bound,” said the barone. “The vampires were yet to be faced in battle, and to refuse to lend any aid to such a design would be wrong in the gods’ eyes.”

“Aye, your highness, you did only what was right,” added Pierozzo. “Besides, the pike and guns would have slowed us to less than half the pace and still made us no more able to defeat such a numerous foe.”

“But it is a king’s duty to protect his realm. First and foremost. In that I have failed.”

“You strove to do exactly that, sire, against the brutes who had torn realm after realm apart, and against the restless dead who threatened far worse,” argued the barone. He gestured at the men before them, “These Sartosans bear all the blame for this deed. Not only are they thieves and murderers, but cowardly opportunists for choosing to strike just when you were engaged elsewhere upon a rightful and necessary war. They will stand before Morr in the end, and he will scorn them.”

“If it is possible for men to be worse than vampires,” said Signore Pierozzo, “then these men are so.”

King Ferronso was not really listening. He squinted as he watched the activity between the trees and the town, where several bodies of men were engaged upon drill practice.

“All is lost,” he repeated. This time his companions said nothing. He sniffed, then turned to the barone. “Vettorio, is all lost?”

“This is bad, sire. But not as bad as it could be. These men have plundered your people, most likely stolen the strongest to sell as slaves. But they won’t eat them as the brutes would have done, nor will they kill them and turn their corpses into foul servants as would the vampires.”

These words did not seem to reassure the king at all. He merely winced at the hearing of them.

“Nor will they stay, your highness,” the barone added quickly. “Sartosans do not conquer, but rather steal what they can, and then move on.”

“So, when they choose to go, I can return to whatever ruins they leave behind?” said the king. “Weeping women and frightened children? Not a scrap of gold to pay my debts, nor a drop of wine to drink, nor even a morsel of mutton for supper?”

“The realm will heal, sire, given time.”

“Yes, I suppose it will,” said Ferronso, somewhat dismissively. “And I am still king.”

His two companions fell silent, at a loss as to what to say to such a child-like remark.

“They have pikes,” the king announced, his sudden tone of curiosity jarring. “I never knew pirates to be pikemen.”

“Aye, sire,” said Signore Pierozzo. “Those are our pikes.”

“Ours?”

“The town militia’s. They must have taken them from the arsenal. Maybe they feared we might return, and well-mounted?”

“If that’s true then they obviously thought there would be more of us,” said the young king.

The three of them then watched the enemy a while. The Sartosans had divided themselves into little companies, all the better to practise with their unfamiliar arms. Each group had a commander, no doubt someone experienced in the handling of a pike, to guide them through their postures, and ensure they could do so as one. Some were busy at the charge, although unusually they did not hold the pikes at their necks but thrust them from their waists like spears.

This struck the barone as odd, for it was not the Tilean way. Perhaps the man in charge was from some far away realm where such a drill was employed? Others stood at order and watched, while a heavily bearded northerner in a huge green coat and an orange scarf, a Marienburger most likely, tested the firmness of one fellow’s grip by pressing at the pike’s extremity.

Still others came up as if just about to join in the practice …

… while one tardy fellow stood by a stand of pikes leaning against a building, trying each one as if deciding which was best.

“There don’t seem to be that many of them,” said the king.

His companions, somewhat judiciously, and knowing the young king well, said nothing.

“But then, I suppose these are just some of them,” he added after a while.

“There are indeed many more, Sire,” said Pierozzo. “Here, in the city and across your realm. They have a great number of handgunners, as well as several batteries of cannons and swivel guns.”

“What guns?” asked the king.

“Small artillery pieces, that are mounted upon stanchions on a ships’ gunwales. Neither handgun nor cannon, but somewhere in between.”

“Yes,” said the king, sounding impatient. “I know those.”

Pierozzo nodded, then continued, “There are dwarfs amongst them, even greenskins …”

The king scowled at this comment, which made Pierozzo stop.

“Go on,” said the king. “What else?”

“And regiments of fighters festooned in weapons of every kind.”

“No armour though?”

“None, sire. I’m led to believe they fear the consequences should they fall into the sea.”

The young king thought about this for a moment. Then he pointed towards three pikeless men who were watching the rest.

“Who are they?” he asked.

“I cannot say, sire. Captains, most likely. At least, one of them.”

“The one in the black coat, I’ll bet,” said the king. “That one by his side in the robes, he’s a wizard, surely?”

“Very probably, sire. And the other one, some lesser officer, a first mate or a Bo’s’un or such like.”

“Would it not be for the best, sire, that we leave now, before we are spotted?” asked the barone. The king did not answer, but just turned and began strolling away. His companions joined him.

“I should not wait until I can creep home, skulking in the shadows in the meantime,” announced the king. “These Sartosans must be punished. What they’ve taken must be retrieved. My people need to know I am a vengeful king, and others must learn what happens to those who offend me.”

“Of course, sire,” said Barone Vettorio, glancing briefly at Pierozzo.

“So, how exactly do I do what must be done?” asked the king.

…

Another excerpt from Bonacorso Fidelibus’s work: “The Many Wars of the Early 25th Century”

Autumn, 2403 continued

In the central parts of the peninsula, war had wracked the realms as would a great wave wrecking all in its path with its passage, both forth and back. The realm of Trantio, ravaged by the War of the Princes, first wasted by the plundering progress of Boulderguts’ brutes, then polluted by the putrid army of the Church of Nagash, had now been captured by the Grand Alliance army commanded by Lord Alessio Falconi of Portomaggiore. Having driven the undead force from the field of battle in the Valley of Norochia, slaughtering many hundreds among the graveyards and tombs, then hacking down all the others they could find fleeing northwards, a large portion of Lord Alessio’s great army had been forced to tarry some time, due to the need to cleanse the realm of corruption. Just as had happened twice at Viadaza, there were thousands of corpses to be destroyed, so that the evil that had animated them might be prevented from doing so again. Great pits were dug for the burning of the corpses in the necropolis valley as the land was re-consecrated, while every corner of every building in the city was scoured for now dead undead. Bones both bloody and dry were piled upon carts, most taken to the valley for burning, but some burned in lesser gardens of Morr within the city precincts. Here and there a severed limb still twitched, a lipless jaw snapped shut, while many a rotting hand would suddenly clutch – a sign that the evil curse pervading the city still lingered. Priests accompanied all the labourers and soldiers as they went about the horrible work, praying incessantly to ensure that the dead remained dead until they could be turned to ash.

By Lord Alessio’s reckoning, not all the undead at Norochia had been caught and killed, so he led the rest of the army, by far the biggest contingent, northwards, moving as rapidly as possible in the hope of catching what fraction of the enemy had escaped. By the time he reached the ruins of the walled town of Scorcio, however, he had come to accept he could not hope to catch the foe, for the enemies’ legs were tireless. Furthermore, both Scorcio and Preto had been as badly tainted as the city of Trantio, and to leave them uncleansed would have been dangerously reckless. And so the great army’s advance was temporarily prevented by the necessities arising from its already achieved successes and progresses.

The last of the enemy, reduced to a mob of once-dedicant zombies, who even in undeath remained frantic and strange in their motions, as well as a company of more ancient, osseous warriors, were commanded by one of the duchess’s favoured servants, her archpriest Biagino. Once he served Morr, gifted by visions and so driven by inspired purpose to be one of the leading agents in the raising of the god’s holy armies, but now, since his capture in battle, he had become a twisted mockery of his once-living self. Running night and day without halt, taking the most barren and inaccessible route to make pursuit all the harder for any who attempted to do so, he led the last, tiny remnant of his army back towards his beloved lady.

Some powerful and wicked sense, a gift of his cursed affliction, directed him towards Ebino, where the Duchess Maria was. She had utterly overwhelmed the army of Morrite dedicants who had marched to face her, killing them to a man. Their bodies lay thickly about the earthwork defences they had fashioned for their camp, along with the cooling corpses of dishonoured Reman palazzio guard (exiled from the city, under Father Carradalio’s command, as a consequence of their inaction during the Discplinati’s seizure of Remas).

While a living commander would have been faced with the inconvenience of clouds of fat flies and the overpowering stench of a thousand corpses requiring burial, she and her necromantic servant Safiro saw only an opportunity to increase her army’s the fighting strength. For many hours, she and foul Safiro conjured dark, magical energies to coalesce within and animate the corpses …

… so that one by one, the once-holy army of the Disciplinati di Morr and the Reman guardsmen struggled to their feet, then staggered, ungainly, away from the defences …

… to muster themselves awkwardly outside, there to await the duchess’s further command.

The unnatural strength and agility possessed by so many vampires allowed (that which was once) Maria to stroll easily, even regally, through the carnage of battle …

… to beckon up the dead with a calmly sinister gracefulness, so that the ultimate fate of blessèd Father Carradalio’s Disciplinati di Morr, in direct opposition to their most painfully earnest goal, was merely to swell the stinking ranks of the duchess’s Ebinan army.

Round and round the horror churned, so that now, yet again, another army would have to be found to face the foe in battle, once again attempting to kill that which was already dead.

In Campogrotta there was a new ruler – or at least a ruler-in-waiting, serving an apprenticeship of sorts before obtaining full possession – for King Jaldeog of Karak Borgo had gifted the entire realm, in a sorry state indeed after the harsh rule of the ogres, to the condottiere commander of the Compagnia del Sole, General Bruno Mazallini. This was done in part as payment of debts, for the king had hired the company to assist in his war against Boulderguts’ lieutenants, but then won the war before the mercenaries arrived. But mostly it was done because it was the quickest and easiest way to promote the realm’s return to health and security. There were contractual clauses to abide by, of course (such is the way of dwarfs), and a good number of King Jaldeog’s bearded servants yet remained in the city as friendly advisers. Within only weeks life in the city was beginning to return to normality.

Yet other hirelings, the Bretonnian Brabanzon, were heading north, with their fiery new commander, the Lady Perrette …

… as well as the still-sickly Baron Garoy and a strong contingent of Karak Borgo warriors, making their way to the realm of Ravola there to drive out the last of Razger Boulderguts’ brute-bullies, left behind when he embarked upon his bloody chevauchee into the heart of Tilea.

In the city the Bretonnians had so recently departed, the taverns were once again filled with men and dwarfs, clattering tankards and puffing upon pipes, as they forgot their troubles and discussed the opportunities ahead of them.

Yet for many a week and more it was only those who came from outside the city who could feel any sort of true happiness. Those who had been in the city during its occupation, much reduced in number and all to a person grieving the loss of neighbours, friends and family, wore haunted looks upon their faces and struggled to find words for even the most mundane moments.

Perhaps some part of them sensed that the apparent return to their old, familiar way of life was merely transitory? That the future held new horrors more than sufficient to rival those of the past? For unknown to almost everyone, sly and sinister agents already inhabited the shadows of the darkest hours, creeping surreptitiously through the streets, hither and thither …

… some to watch, others to whisper; and the hour of their coming, for which they had long prepared with complex machinations and conspiracies so deep as to be unfathomable, was at hand.

Bloody Guidobaldo!

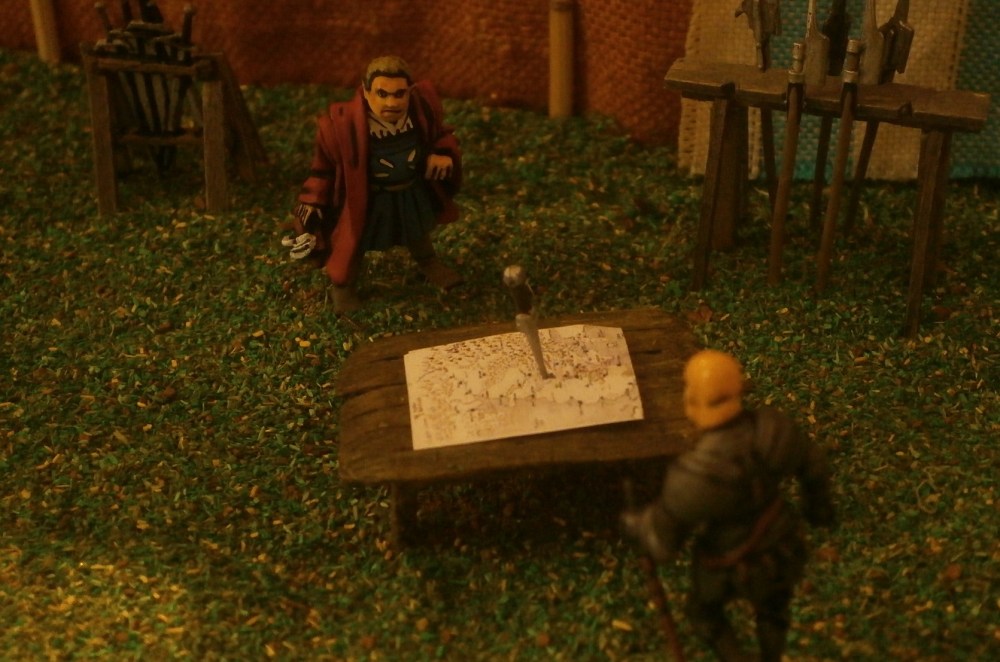

Note: This little story was originally drafted by the player who commands Portomaggiore, which is only fitting as it involves a conversation between his own player character, Lord Alessio Falconi, and his closest adviser (an NPC). It was then re-written by me to better fit the campaign’s ‘writing style’ (i.e. my writing style). Much was swapped around, but little was changed in terms of the substance of what the characters said. I did change a bullet hole in a map into a knife, but that was for the picture’s sake … after all, who would even have been able to see a minuscule, pin-prick bullet hole in a map actually measuring 1 cm by 1.5 cm?

There is only one picture, but I reckon sometimes just one picture is just right!

The story …

A TENT IN THE MIDDLE OF WAR

Somewhere in the realm of Trantio, at the end of Autumn 2403

Lord Alessio was glad he was alone. The flash of fury that had just driven him to thrust his knife into the table …

… was not something he would wish his servants and officers to see. He had a reputation for calm, self-control to maintain. Still, he thought, he need not reproach himself for his impetuousness, for the news he had received would drive even the most meditative of monks to distraction. If his weakness was nothing more than the mere momentary desire to stick a knife into a map, then it truly paled into insignificance when compared to the weakness of the man whose actions had instigated his anger – Duke Guidobaldo of Pavona.

As the anger subsided, which it quickly did, he looked at the knife and chuckled. It had struck the map exactly where he intended, obliterating the inked name of Pavona in the process.

Movement at the entrance of the tent caught his eye, and he looked up to see Lord Black leaning into the tent.

“My Lord,” said his visitor. “May I?”

Alessio gestured to his friend to enter. As Lord Black strode in he looked at the knife.

“I see you’ve heard the news,” he said, apparently understanding immediately what had just happened. “It never rains but it pours, eh? First the Sartosans sap us of the Luccinans, and now the soldiers of the VMC have become distracted by a sudden need to make war against Pavona.”

“We are attempting to fight a war to save all of Tilea, Ned,” said Alessio, “against the enemy of life itself. And what does every other Tilean ruler do to help?”

“They set about attacking each other?”

“Of course! What else?”

Ned leaned upon his scabbarded sword and looked at the map. “Well, at least they’re all willing to fight,” he said.

Alessio gave a pained chuckle.

“So, what do we do?” asked Ned.

Alessio pondered a moment, then spoke, “As I see it, we have three options. We could march to Pavona in an attempt to convince the VMC not to sack the city, and deal with the duke later.”

“So, you don’t believe his claim that the VMC murdered Lord Lucca?”

Alessio just rolled his eyes, then continued, “Or we could leave them both to their misery and return home. Whichever squabbling fools survive would then have to face the duchess themselves.”

“Aye, and if they lose their battle for want of sufficient strength, we will be forced to fight their walking corpses later, after the duchess makes them her own.”

“Which leads me to the third option,” said Alessio. “We can press on regardless, with just the forces we have at our disposal. Try our luck against the duchess despite our lack of allies.”

“Several have tried that before without success. Do you think the army the duchess commands is as strong as that we defeated in Norochia?”

“Considering she wiped out an entire horde of fanatical Morrites at Ebino, she cannot lack in strength. I had thought of sending word to the mountain dwarves and the Compagnia del Sole to request that they dispatch a force to join us, but I strongly suspect they’re still too distracted by the recapture of Campogrotta and the need to deal with the brutes remaining in Ravola.”

“We might have struggled to feed them, anyway,” said Lord Black.

“Well, now that Verezzo has been so grievously wounded, we can hardly expect their payments to continue, which makes feeding what we already have more difficult. I like and respect Lord Silvano, as you know, but his father has picked a terrible time to pull one of his bloody tricks.”

“One would hope, my lord, that the VMC had been here long enough to learn that revenge is a dish best served cold.”

Lord Alessio merely rolled his eyes at the suggestion.

“Can we not cut spending at home for a while?” asked Ned. “Do we need a new harbour right now? Cannot Hakim wait a little longer for his magical lighthouse to be completed? And, in light of the threat, even the Ravernans might be willing to show patience over the pace of the works in their realm.”

“We could save gold that way, yes” agreed Alessio, “but if the Sartosans move north then that gold will still be needed at home.”

“So, what do we do?” asked Ned, again.

Alessio looked at the map and sighed.

“Whatever is best,” he said.

…

Next Installment: Part 26